Will Economic Growth Cease to need Human Labor by 2030?

The question of whether economic growth will completely decouple from human labor by 2030 represents one of the most consequential inquiries of our era, demanding examination through multiple analytical lenses—historical, technological, regional, and socioeconomic. Current evidence suggests we are witnessing the early stages of a potentially unprecedented economic transformation, though complete decoupling within this timeframe appears improbable despite accelerating trends toward partial separation. Consider the concept of labor decoupling.

Historical Context and Contemporary Acceleration

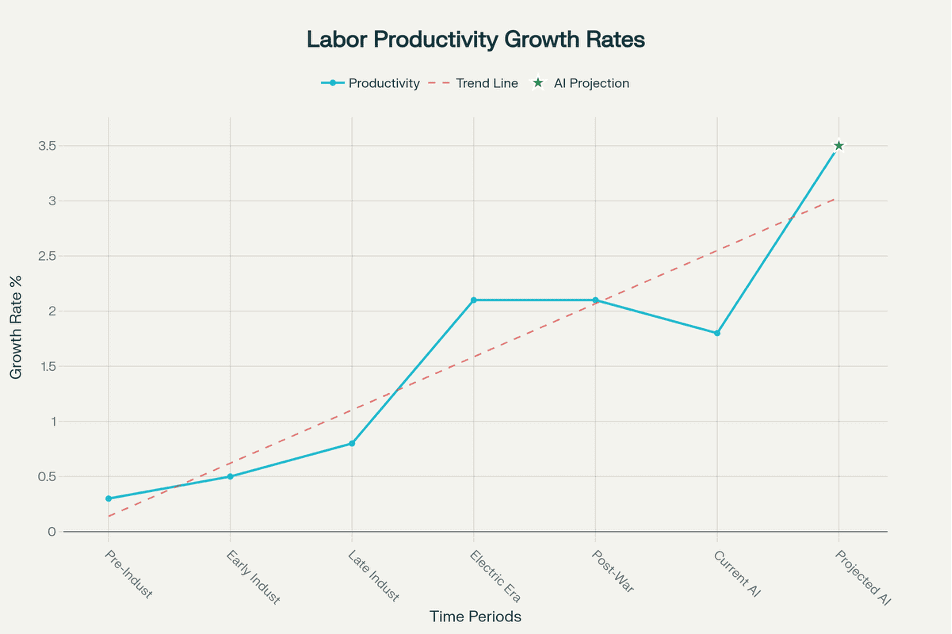

The relationship between productivity growth and employment has undergone dramatic shifts throughout human history, with each technological revolution presenting unique characteristics and timelines. During the pre-industrial period from 1700 to 1780, productivity growth averaged merely 0.3 percent annually. The Industrial Revolution marked the beginning of sustained productivity acceleration, with growth rates rising to 0.5 percent during the early industrial period (1780-1830) and reaching 0.8 percent by the late industrial era (1830-1860).[1][2][3]

Historical productivity growth shows potential AI-era acceleration beyond past technological revolutions

The electricity era of 1899-1929 represented a quantum leap, achieving productivity growth of 2.1 percent annually in manufacturing. This period established a pattern that persisted through the post-war growth era (1947-2007), maintaining similar productivity growth rates of approximately 2.1 percent. The current AI era, beginning around 2019, has shown productivity growth of 1.8 percent annually, representing a slight deceleration from historical peaks despite technological advancement.[2][4]

However, projections for the remainder of this decade suggest a dramatic departure from historical trends. Economic models incorporating AI capabilities anticipate productivity growth rates potentially reaching 3.5 percent annually by 2025-2030, surpassing even the transformative electricity era. This acceleration reflects fundamental differences between current AI technologies and previous automation waves.[5][6]

Current Evidence of Emerging Decoupling

Contemporary data reveals compelling evidence of nascent decoupling patterns, particularly affecting specific demographic and occupational segments. Stanford research analyzing payroll records from millions of American workers has documented a 13 percent relative decline in employment for early-career workers (ages 22-25) in AI-exposed occupations since late 2022. This represents an unprecedented speed of labor displacement, occurring within months rather than the decades typically associated with previous technological transitions.[7][8]

The scope of this emerging decoupling extends beyond individual job categories. Recent labor statistics reveal that while the U.S. economy maintained GDP growth rates approaching 4 percent, job creation has stagnated dramatically. The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ preliminary benchmark revision reduced estimated job growth by 911,000 positions between March 2024 and March 2025, effectively negating approximately half of previously reported employment gains.[9][10][11]

This phenomenon of “jobless growth” represents a concerning departure from traditional economic relationships. Prime-age labor force participation has remained elevated compared to 2023 levels, yet unemployment has risen to 4.3 percent as of August 2025, the highest rate since 2021. The economy added merely 22,000 jobs in August 2025, falling significantly short of economist predictions of 76,500 positions.[12][13]

Technological Drivers and Capabilities

The technological foundations underlying potential economic-labor decoupling differ qualitatively from previous automation waves. Unlike mechanical automation that typically affected routine manual tasks, contemporary AI systems demonstrate capabilities across cognitive domains previously considered uniquely human. Generative AI technologies have shown proficiency in complex reasoning, creative tasks, and knowledge synthesis—capabilities that encompass broad swaths of professional occupations.[14][6]

Research from Epoch AI suggests that AI systems capable of broadly substituting for human labor could plausibly accelerate economic growth by an order of magnitude, potentially reaching 40 percent annual growth rates. This projection, while speculative, reflects the scalable nature of digital labor forces that can expand without the biological and educational constraints governing human workforce development.[5]

The economic impact mechanisms driving this potential decoupling operate through multiple channels. Productivity gains emerge from process automation and workforce augmentation, while consumption-side effects result from personalized, higher-quality AI-enhanced products and services. PwC research estimates that AI could contribute up to $15.7 trillion to the global economy by 2030, equivalent to the combined current output of China and India.[6]

Regional Variations and Implementation Patterns

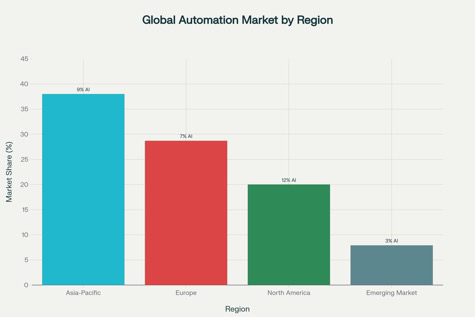

Global implementation of automation and AI technologies reveals significant regional disparities that will influence decoupling trajectories across different economic zones. Asia-Pacific dominates the automation market with 38 percent global market share and an 11 percent compound annual growth rate through 2030. However, North America leads in AI/ML application rates at 12 percent, compared to Europe’s 7 percent and Asia-Pacific’s 9 percent.[15][16][17]

Regional automation market distribution reveals Asia-Pacific dominance despite lower AI adoption than North America

These regional differences reflect distinct strategic priorities and economic pressures. North American manufacturers pursue automation primarily for labor replacement and efficiency optimization, driven by higher wages and skills gaps. European approaches emphasize precision engineering and sustainability, balancing automation adoption with worker protection policies and environmental considerations. Asia-Pacific strategies focus on rapid deployment at massive scale, leveraging government initiatives like China’s “Made in China 2025” program.[15][17]

Emerging markets face unique constraints in pursuing automation-driven decoupling. With substantial labor surpluses and lower wage costs, these economies must balance automation adoption with job creation imperatives. Africa’s projected population growth to 2.4 billion by 2050 creates demographic pressures that favor employment-intensive rather than labor-displacing technologies.[15]

Industry-Specific Displacement Patterns

Analysis of sectoral impacts reveals uneven progression toward labor decoupling across different economic domains. Manufacturing productivity increased 2.5 percent in Q2 2025, reflecting continued automation penetration. The World Economic Forum projects that 40 percent of employers expect workforce reductions in areas where AI can automate tasks.[14][4]

Financial services, healthcare, and retail emerge as sectors with greatest AI disruption potential. Banking operations increasingly rely on automated underwriting and fraud detection, while healthcare adopts AI-powered diagnostics and drug discovery platforms. These transitions occur rapidly within specific functions while leaving other operational areas relatively unchanged.[6][16][18]

Service sector automation presents complex dynamics. While customer service, data processing, and routine administrative tasks face displacement, demand grows for AI-complementary roles requiring human judgment, creativity, and interpersonal skills. This pattern suggests sectoral rather than economy-wide decoupling in the near term.[19][14]

Counterbalancing Forces and Limitations

Several structural factors constrain the pace and extent of potential economic-labor decoupling by 2030. Regulatory frameworks across major economies remain largely unprepared for rapid automation adoption. The European Union pursues strict risk-based AI regulations, while the United States relies on industry self-regulation, and Asian nations implement diverse approaches tailored to national priorities.[20][21][22]

Economic evidence from recent periods suggests that productivity growth historically correlates with overall employment expansion rather than displacement. World Bank analysis demonstrates that while automation displaces specific tasks, productivity gains typically increase aggregate demand for goods and services, creating new employment opportunities. This relationship, termed the “reinstatement effect,” has historically offset automation’s displacement impact.[23][24][25][26][27]

Infrastructure and implementation constraints further limit decoupling speed. Despite aggressive AI investment, current enterprise adoption remains modest, with approximately 9.3 percent of U.S. enterprises actively using AI in operations as of 2024. The transition from pilot programs to full operational deployment requires substantial time and capital investment.[18]

Capital accumulation bottlenecks present additional constraints. Bain & Company analysis suggests that by 2030, AI companies will require $2 trillion in combined annual revenue to fund computing infrastructure meeting projected demand. These capital requirements may constrain the pace of AI deployment across economic sectors.[28]

Socioeconomic and Policy Dimensions

The potential for economic-labor decoupling raises profound questions about income distribution and social stability. Current trends show wages decoupling from productivity gains across OECD countries, with labor’s share of national income declining in two-thirds of analyzed nations. This “great decoupling” predates AI adoption, suggesting underlying structural shifts in economic relationships.[29][30]

Policy responses vary significantly across jurisdictions. Some economists advocate for automation taxes to slow displacement rates and fund worker transition programs. Trade Adjustment Assistance programs provide models for supporting displaced workers, though these initiatives have shown mixed effectiveness. Universal basic income proposals gain attention as potential responses to widespread labor displacement, though implementation challenges remain formidable.[21][20]

Employment transitions require substantial retraining investments. McKinsey research indicates that between 400 million and 800 million individuals globally may need new employment by 2030 due to automation, with 75 million to 375 million requiring occupational category switches. The scale of required workforce transformation exceeds historical precedents.[31][32]

Expert Perspectives and Scenarios

Leading economists and technologists present divergent assessments of decoupling timelines and implications. Computer science professor Roman Yampolskiy warns of potential 99 percent unemployment by 2030, arguing that AI capabilities will make human labor economically unviable across virtually all sectors. This represents the most extreme projection, suggesting complete decoupling within the timeframe.[33]

Conversely, research from Yale University’s Budget Lab found no evidence of economy-wide AI displacement through 2025, despite widespread adoption of generative AI technologies. This analysis suggests that while AI impacts specific occupations and worker segments, broader economic patterns remain stable.34,35

Robin Hanson’s economic modeling of machine intelligence scenarios projects more gradual transitions, with economic doubling times shifting from current rates to monthly or yearly cycles as AI capabilities expand. These models anticipate substantial economic acceleration without immediate complete labor obsolescence.[36][37]

The Brookings Institution presents intermediate scenarios, projecting continued full employment through 2030 with rapid worker redeployment rather than widespread unemployment. These projections assume effective policy responses and successful workforce adaptation programs.[31]

Critical Areas of Uncertainty

Several crucial variables will determine whether economic growth decouples completely from human labor by 2030. The pace of AI capability advancement remains highly uncertain, with potential breakthroughs in artificial general intelligence dramatically altering trajectories. Current large language models, while impressive, fall short of human-level reasoning across diverse domains.[38][33]

Regulatory responses represent another critical uncertainty. Government policies could substantially accelerate or constrain automation adoption through taxation, labor protections, or technology restrictions. International coordination on AI governance remains limited, creating potential for regulatory arbitrage.[39][20]

Social acceptance of automation varies across cultures and economic systems. European emphasis on worker protections contrasts sharply with Silicon Valley’s disruption-oriented approach. These cultural differences may produce divergent decoupling patterns across regions.[22][15]

The emergence of new job categories complementing AI capabilities presents perhaps the greatest uncertainty. Historical technological transitions generated employment in previously unimaginable sectors—from software development to social media management. Whether AI will similarly create new human-centric occupations remains unknown.[40][41]

Synthesis and Implications

Current evidence suggests that while economic growth is beginning to decouple from human labor in specific sectors and demographics, complete decoupling by 2030 remains unlikely across the entire economy. The most probable scenario involves accelerating partial decoupling, with certain industries and job categories experiencing rapid labor displacement while others maintain human-centric operations.

Several factors support this assessment. First, the heterogeneous nature of economic activity means that automation adoption will proceed unevenly across sectors, regions, and firm sizes. Small businesses, service industries requiring human interaction, and creative professions may maintain labor intensity even as manufacturing and routine cognitive work become increasingly automated.

Second, the scale of required infrastructure investment and organizational transformation suggests gradual rather than sudden transitions. While AI capabilities are an accelerant to the great decoupling, their integration into complex economic systems requires substantial time and resources. The current productivity growth rate of 1.8 percent annually may accelerate but is unlikely to reach the extreme projections necessary for complete decoupling within five years.[4]

Third, policy responses and social adaptation mechanisms provide feedback loops that may moderate decoupling speed. Democratic societies retain capacity to influence automation trajectories through regulation, taxation, and public investment strategies. The political economy of technological change typically involves negotiation and gradual adjustment rather than wholesale transformation.

However, the direction of change appears clear. The combination of advancing AI capabilities, economic pressures favoring automation, and demonstrated displacement effects in early-career workers suggests that substantial decoupling will occur by 2030, even if incomplete. This partial decoupling may prove more challenging than complete separation, creating persistent unemployment for displaced workers while generating prosperity concentrated among technology owners and AI-complementary workers.

The ultimate resolution of this transformation will depend on choices made in the remainder of this decade. Policy frameworks, investment priorities, and social responses to technological change will determine whether economic growth increasingly detaches from broad-based employment or maintains connections through new forms of human-AI collaboration. The question is not merely whether decoupling will occur, but how societies will manage its consequences and distribute its benefits.

The implications extend far beyond employment statistics to fundamental questions about economic organization, social purpose, and human agency in an age of artificial intelligence. While complete decoupling by 2030 appears improbable, the trajectory toward that outcome has already begun, making this decade crucial for shaping the economic relationships that will define the remainder of the century.

⁂

- https://www.ifo.de/DocDL/cesifo1_wp10766.pdf

- https://www.frbsf.org/wp-content/uploads/crafts.pdf

- https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/antras/files/dualrevind.pdf

- https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/prod2.pdf

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/2309.11690.pdf

- https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/analytics/assets/pwc-ai-analysis-sizing-the-prize-report.pdf

- https://digitaleconomy.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Canaries_BrynjolfssonChandarChen.pdf

- https://fortune.com/2025/08/26/stanford-ai-entry-level-jobs-gen-z-erik-brynjolfsson/

- https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/how-explain-4-growth-no-jobs-2025-09-30/

- https://www.investopedia.com/the-economy-just-lost-nearly-a-million-jobs-on-paper-11806319

- https://www.nbcnews.com/business/economy/911000-fewer-jobs-created-april-2024-march-2025-bls-says-rcna230065

- https://www.epi.org/blog/assessing-the-strength-of-the-labor-market-preliminary-downward-revisions-do-not-necessarily-signal-a-weaker-2024-labor-market-but-there-are-warning-signs-for-2025/

- https://www.cnn.com/business/live-news/us-jobs-report-august-2025

- https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/04/ai-jobs-international-workers-day/

- https://www.eclipseautomation.com/global-automation-perspectives-regional-manufacturing-strategies/

- https://finance.yahoo.com/news/ai-disruption-global-overview-report-110300034.html

- https://www.arcweb.com/blog/industrial-ais-regional-divide-north-america-charges-ahead-europe-hesitates-asia-catches-0

- https://privatebank.jpmorgan.com/nam/en/insights/markets-and-investing/a-new-wave-of-ai-led-disruption

- https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-future-of-jobs-report-2025/digest/

- https://home.dartmouth.edu/news/2022/06/study-slowing-down-automation-may-have-economic-benefits

- https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/how-government-can-embrace-ai-and-workers

- https://www.technical-leaders.com/post/ai-accountability-us-vs-eu-vs-asia

- https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/jobs/what-were-reading-about-productivity-growth-and-jobs

- https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/productivity-employment-nexus-micro-macro-insights-13-countries

- https://docs.iza.org/dp12293.pdf

- https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/10.1257/jep.33.2.3

- https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/jobs/What-we-re-reading-about-the-age-of-AI-jobs-and-inequality

- https://finance.yahoo.com/news/why-fears-trillion-dollar-ai-130008034.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decoupling_of_wages_from_productivity

- https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/decoupling-of-wages-from-productivity_d4764493-en.html

- https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/jobs-lost-jobs-gained-what-the-future-of-work-will-mean-for-jobs-skills-and-wages

- https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/public and social sector/our insights/what the future of work will mean for jobs skills and wages/mgi-jobs-lost-jobs-gained-executive-summary-december-6-2017.pdf

- https://www.businessinsider.com/ai-safety-pioneer-predicts-ai-could-cause-99-unemployment-by-2030-2025-9

- https://www.brookings.edu/articles/new-data-show-no-ai-jobs-apocalypse-for-now/

- https://budgetlab.yale.edu/research/evaluating-impact-ai-labor-market-current-state-affairs

- https://intelligence.org/files/IEM.pdf

- https://philpapers.org/rec/HANEGG

- https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/77xLbXs6vYQuhT8hq/why-ai-may-not-foom

- https://www.michaeldavidmangini.com/publications/robots-trade/chaudoin_mangini_robots_trade.pdf

- https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/five-lessons-from-history-on-ai-automation-and-employment

- https://www.weforum.org/stories/2020/09/short-history-jobs-automation/

- https://ppl-ai-code-interpreter-files.s3.amazonaws.com/web/direct-files/26576684ff446abbc2a2f80342a2dba4/c6d6b7ca-279d-4d27-8ed5-894961120281/2f3a7f97.csv

- https://daveshap.substack.com/p/post-labor-economics-pt-i-the-rise

- https://www.brookings.edu/articles/u-s-productivity-growth-an-optimistic-perspective/

- https://natesnewsletter.substack.com/p/the-great-decoupling-labor-growth

- https://www.cnn.com/2025/10/01/business/ai-impact-us-jobs-study-intl

- https://www.economicstrategygroup.org/publication/in-brief-us-labor-productivity/

- https://shapingwork.mit.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/acemoglu-restrepo-2019-automation-and-new-tasks-how-technology-displaces-and-reinstates-labor.pdf

- https://cepr.net/publications/downward-job-revision-means-strong-productivity-upturn-under-biden/

- https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/artificial-intelligence/ai-jobs-barometer.html

- https://www.britannica.com/story/the-rise-of-the-machines-pros-and-cons-of-the-industrial-revolution

- https://ide.mit.edu/insights/the-emerging-unpredictable-age-of-ai/

- https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/inline-files/Why Are there Still So Many Jobs_0.pdf

- https://www.8vc.com/resources/the-future-of-labor-keynes

- https://www.familywealthlibrary.com/post/john-maynard-keynes/

- https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2022/article/growth-trends-for-selected-occupations-considered-at-risk-from-automation.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrial_Revolution

- https://www.technologyreview.com/2024/01/27/1087041/technological-unemployment-elon-musk-jobs-ai/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/CapitalismVSocialism/comments/os7b5l/since_the_industrial_revolution_the_productivity/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technological_unemployment

- https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/what-past-waves-of-automation-can-teach-us-about-ai/

- https://eml.berkeley.edu/~enakamura/papers/malthus.pdf

- http://www.econ.yale.edu/smith/econ116a/keynes1.pdf

- https://www.reddit.com/r/Futurology/comments/1l0nvfr/im_struggling_to_see_how_the_argument_of/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/AskFoodHistorians/comments/1hku0g5/did_coffee_and_tea_actually_affect_the/

- https://www.marketplace.org/story/2025/08/07/did-labor-productivity-really-grow-in-q2

- https://set.kellyservices.us/resource-center/a-labor-market-mystery

- https://www.epi.org/productivity-pay-gap/

- https://www.bls.gov/productivity/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2542519623001742

- https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R48695

- https://datatopics.worldbank.org/sdgatlas/archive/2017/SDG-08-decent-work-and-economic-growth.html

- https://www.atlantafed.org/blogs/macroblog/2025/10/01/digging-deeper-into-declining-labor-force-participation

- https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf

- https://ourworldindata.org/energy-gdp-decoupling

- https://wealthcreationmastermind.com/blog/the-automation-scenarios-predicting-the-impact/

- https://www.brookings.edu/articles/who-will-lead-in-the-age-of-artificial-intelligence/

- https://www.nexford.edu/insights/how-will-ai-affect-jobs

- https://timothyblee.com/2011/01/17/reply-to-hanson-on-brain-emulation/

- https://www.futuresplatform.com/blog/future-of-work-ai-in-the-workplace-scenarios

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/sentient-ai-societies-implications-human-civilization-andre-5fjxe

- https://www.shrm.org/topics-tools/news/all-things-work/technology-future-work-way-will-go

- https://www.privatebank.bankofamerica.com/articles/economic-impact-of-ai.html

- https://www.slatestarcodexabridged.com/Book-Review-Age-Of-Em

- https://www.brookings.edu/articles/ai-labor-displacement-and-the-limits-of-worker-retraining/

- https://business.uq.edu.au/momentum/4-ways-ai-will-revolutionise-the-world

- https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/267450/1/dp15713.pdf

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/where-north-america-stands-automation-global-comparison-ezofis-gxdbc

- https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/the-economic-potential-of-generative-ai-the-next-productivity-frontier

- https://www.aspeninstitute.org/programs/future-of-work/automation/

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ais-global-race-how-regional-differences-shaping-future-barry-hillier-ji73c

- https://www.janushenderson.com/en-us/institutional/article/how-ai-disruption-is-reshaping-the-software-sector-landscape/

- https://www.brookings.edu/articles/automation-a-guide-for-policymakers/

- https://www.anthropic.com/research/anthropic-economic-index-september-2025-report

- https://www.rbcwealthmanagement.com/en-asia/insights/ais-big-leaps-in-2025

- https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2024/06/17/fiscal-policy-can-help-broaden-the-gains-of-ai-to-humanity

- https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/eap/publication/future-jobs

- https://tech.us/blog/artificial-intelligence-and-the-four-stages-of-disruption

- https://ppl-ai-code-interpreter-files.s3.amazonaws.com/web/direct-files/26576684ff446abbc2a2f80342a2dba4/c6d6b7ca-279d-4d27-8ed5-894961120281/77ed23c7.csv

- https://ppl-ai-code-interpreter-files.s3.amazonaws.com/web/direct-files/26576684ff446abbc2a2f80342a2dba4/c6d6b7ca-279d-4d27-8ed5-894961120281/e64e6144.csv

This essay is part of the research foundation for The Theory of Recursive Displacement — a unified framework examining how AI-driven automation reshapes labor markets, capital flows, governance structures, and human economic agency. Read the full theory for the complete analysis.

Ask questions about this content?

I'm here to help clarify anything