A Token for Me a Token for You

Introduction

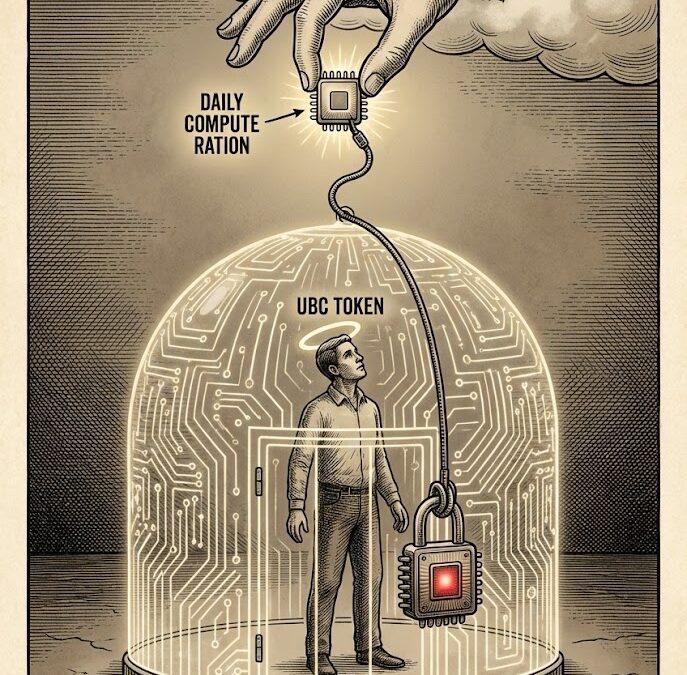

Imagine a future where Universal Basic Compute (UBC) replaces Universal Basic Income (UBI) as the social safety net. Instead of monthly checks, you receive a monthly ration of computing power – a guaranteed slice of AI’s capabilities, like getting a share of GPT-7’s processing time. Proponents hail UBC as a forward-thinking antidote to automation-driven inequality: if AI and robots produce most value, why not give everyone access to the “means of production” in compute rather than just cutting checks? UBC is framed as a progressive entitlement, promising to democratize the very fuel of the AI era. But lurking beneath the utopian veneer is a structural transformation of power, agency, and rights – one that risks turning existence itself into the primary metered resource of a post-labor society. This essay argues that Universal Basic Compute is a trap: a tokenization of everyday life that could lock individuals into a closed loop of dependence and control. We’ll explore how UBC differs from UBI, how tokenizing life creates new forms of domination, historical analogues that forewarn of the risks, and the dire consequences for human autonomy and meaning. Finally, we’ll consider what safeguards or alternatives might avert this dystopian outcome. The goal is not to oppose the idea of equitable tech access, but to illuminate how even a well-intentioned policy can be architected as a tool of extraction and control. Now let us dissect the tokenization of existence with clear eyes and urgent clarity.

From UBI to UBC – Progressive Promise or Digital Scrip?

Universal Basic Income (UBI) is simple: give everyone a regular cash stipend, no strings attached, to ensure a minimal standard of living. UBC, on the other hand, proposes to give everyone a baseline amount of computational resources – processing power, storage, AI services – as a public good. Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, popularized UBC by suggesting “everybody gets like a slice of GPT-7’s compute” which they can use, resell, or donate. In Altman’s view, as AI systems become the engines of wealth, owning a piece of that compute could be more valuable than money, effectively giving each person ownership of part of AI’s productivity. UBC is portrayed as a techno-progressive evolution of UBI: rather than just mitigating poverty, it empowers people with the tool that creates wealth in an AI-driven economy. Advocates argue that UBI alone may fall short in a world where access to technology determines opportunity. Why give fish, when you can give a fishing rod – or so the logic goes.

On the surface, this sounds inspiring. Access to computation could be as crucial in the 21st century as access to electricity or clean water. Indeed, some have begun calling for the ”right to compute” akin to a human right, equating computational access with freedom of thought and expression. Montana even passed a Right to Compute Act protecting citizens’ rights to use computing tools on their own property, framing computers as extensions of the human mind and their use as an essential liberty. All this lends UBC a progressive sheen. It feels like a natural next step: if automation is displacing jobs, give people the means to generate value (compute power) rather than a passive income. In theory, UBC could spur innovation from below, as billions of individuals, armed with AI capabilities, create, invent, and solve problems. It could narrow the AI divide and prevent a world where only tech giants and the ultra-rich benefit from artificial intelligence.

Yet, UBC fundamentally differs from UBI in one critical way: it doesn’t give you a self-sufficient asset – it gives you tokens usable only within a specific infrastructure. UBI dollars can be spent anywhere; UBC credits likely must be spent on the sanctioned compute network, AI services, or digital platforms that honor them. You can’t eat compute; you must convert it or use it via approved channels to meet your needs. This is where the alarm bells begin to ring. UBC might create a new kind of currency that looks empowering but behaves like company scrip: valuable only in the company store of whoever runs the compute allocation. It is a short step from a progressive entitlement to a high-tech leash. To see why, let’s examine how tokenizing our lives under UBC could reshape every facet of society – and not for the better.

Tokenization: When Every Bit of Life Becomes a Metered Asset

UBC, at its core, is about tokenizing compute – turning computing power into a quantifiable unit that is distributed and tracked. But the tokenization doesn’t stop at GPU cycles. In a fully UBC-driven system, everyday life begins to translate into computational transactions. Need an AI to help you study or create art? Spend a bit of your UBC credit. Want your smart home to cook, clean, and manage your schedule? Those services are metered by your compute allocation. Even social interactions might be mediated by AI assistants (for scheduling, translation, etc.), dipping into your compute wallet. The fabric of existence turns into a series of metered events, each with a token value attached.

Consider what this means. Previously intangible aspects of life – a conversation, a decision, a creative impulse – could now have a compute cost associated. If you have a limited compute budget, you start rationing and optimizing your life around those tokens. In effect, life becomes legible to the system as a series of billable actions. This is digital Taylorism for the self: optimizing how you “spend” your allotted compute on tasks and interactions. What isn’t measured in this way might simply be unsupported – e.g. non-digital or analog activities might fade in relevance or become luxuries, since all essential services are tied into the compute economy.

This dynamic recalls what Shoshana Zuboff famously termed surveillance capitalism, “an extractive political economy built on the systematic capture and monetization of human experience”. Under UBC, the monetization goes beyond targeted ads. Your very ability to act – to use tools, to interface with society – is metered. Human experience becomes computer experience: a feedstock for AI systems and a source of data and fees. Every move you make in the digital world (and under IoT, the physical world too) can generate data, requiring compute and thus expending tokens. The feedback loop is rich for exploitation: providers of UBC can monitor what people do with their compute, glean valuable behavioral data, and even shape behavior by how they design the pricing and availability of services.

In a tokenized existence, your life is effectively sliced into token-denominated units. Much like how a gig economy worker’s time is chopped into task-based payments, an individual in a UBC world could see their daily routines chopped into AI-mediated microtransactions. The danger here is subtle but profound: once life is fully tokenized, those tokens can be used to steer and constrain behavior. If certain activities “cost” too many tokens, you’ll avoid them; if an AI service is cheap or free, you might over-rely on it and let it shape your habits. What’s presented as a free baseline of compute could easily become a carefully budgeted ration that you must spend judiciously to navigate life, always aware that some activities are “off budget.” The currency of UBC might be new, but the effect is age-old: dependence. To understand the trap of dependence, we turn to history – to company towns and feudal estates – which offer an eerie parallel to UBC’s promise.

A Closed-Loop of Dependence: The Company Town Reborn

“What the lord giveth, the lord taketh away.” In feudal times, peasants lived on the lord’s land, survived by his permission, and in return gave up a share of their harvest and freedom. Their existence was in a closed loop: they depended on the lord’s land and protection, and thus could be controlled by the terms he set. Fast forward to the 19th-century company town: a coal miner is paid in company scrip – private currency usable only at the company-owned store and housing. The miner’s shelter, food, tools, and even doctor are all provided by the company, with scrip deducted from wages. It was a self-contained economic loop designed to bind the worker to the employer. “Since company scrip could only be used at company stores, it gave companies a monopoly over their workers and made the workers dependent on the company,” as one history source notes. Miners often ended up in perpetual debt to the company, “another day older and deeper in debt,” to quote the song “Sixteen Tons.”

UBC threatens to digitally resurrect the company town model on a global scale. In the UBC company town, your income isn’t cash – it’s compute tokens. And whose “store” accepts these tokens? Likely a platform or network managed by a consortium of tech providers or the state. Need groceries or rent? Perhaps you convert some compute tokens via an approved exchange (with fees, of course) to get them – analogous to how miners sometimes exchanged scrip for cash at a terrible rate. More likely, essential goods and services themselves might be integrated: e.g. an AI manages your pantry and automatically orders food, which is delivered by autonomous drones – and all those steps consume some of your compute allocation. It’s the company store in clever disguise. As long as you operate within the system, things might feel convenient. But try to step out – to use your resources outside the sanctioned ecosystem – and the true dependency reveals itself.

Historically, company scrip systems were justified by practical constraints (remote mining towns had no cash economy) but exploited to monopolize and control. Companies often overcharged for goods or lodged workers in overpriced housing, knowing workers had no alternative. Critics of the coal scrip system noted that when workers rely on a single retailer, that company can “charge exorbitant prices or sell inferior goods,” leaving workers perpetually vulnerable. In one account, coal companies even cut off miners’ store credit and evicted them from company housing when they tried to unionize or seek better jobs – a retaliatory move only possible because every aspect of those miners’ lives was tethered to the company’s domain.

Now transpose this to UBC. If a single network or a few coordinated platforms control the infrastructure through which UBC tokens have value, they hold similar power. They can dictate prices for digital services, from education to entertainment, effectively deciding how far your compute ration goes. They could prioritize their own “stores” (services) over potential competitors, since your token might not be accepted elsewhere. And, chillingly, they could cut you off with the flick of a switch if you become a “problem.” In a company town, getting fired meant not only loss of income but often immediate eviction – you lost your home, your currency became worthless, you might even be forced out of the town gates. In a UBC regime, getting “fired” could mean your digital identity and compute credits are suspended. Overnight, you’d lose access to AI assistance, perhaps to your IoT-connected home functions, to digital payment systems, maybe even to self-driving transport if that is tied to the same ID. Your existence, so thoroughly tokenized, can be shut down.

It’s important to note that UBC doesn’t necessarily mean only private corporations run it – it could be a state-run system or a public-private partnership. But either way, it introduces a middleman between you and basic resources. Instead of a government giving you cash (which you control how to spend), it gives you a voucher for compute that must be redeemed within the state’s or provider’s ecosystem. Vouchers have a way of constraining and demeaning the poor (think food stamps with limited usability). Now imagine everyone is forced to live on vouchers, for everything. That’s UBC’s closed loop: an ostensibly benevolent provider meeting all your needs within one enclosed, fully metered bubble.

We have analogues in the digital sphere already. Consider the way we depend on big tech platforms for digital services and how that dependence can be abused. Scholars have described a kind of “digital feudalism” today, where tech giants are the lords of online platforms and we are the vassals. Facebook, Google, Amazon – they offer us digital “land” (social media spaces, cloud storage, marketplaces) to inhabit, and in return we till their fields by producing data and content which they harvest for profit. In this arrangement, users can feel locked in – leaving Facebook, for instance, means losing your social connections; leaving Amazon might mean losing access to convenient shopping or self-publishing markets. Now, add UBC to this mix: the platform isn’t just where you socialize or shop; it’s where you derive your very means of transaction. You would become even more of a “digital serf,” as one writer put it, “sending your data as tribute up the pyramid to digital lords” – except now the tribute includes the record of every compute token you spend. UBC could formalize digital feudalism by making each citizen’s livelihood (in compute credits) contingent on continued allegiance to the digital realm’s rules.

In summary, UBC risks creating a self-contained economy of dependency. It’s a closed loop where the provider of the resource (compute) controls the uses of that resource, the terms of trade, and even the units of value themselves. History shows that when workers were paid in isolated currencies (company scrip), exploitation followed and freedom was curtailed. A future where citizens subsist on UBC tokens could recapitulate those injustices on an unprecedented scale. To see the full dimensions of control at play, we need to unpack the layers of infrastructure that underlie UBC – from who produces the compute to how it’s allocated – and how those layers can be leveraged to reshape agency and rights.

The New Infrastructure of Control: Production, Allocation, and Agency

To understand the structural power of UBC, consider the stack of infrastructure it rests upon:

- Production of Compute: Who owns and runs the data centers, AI models, and networks that provide the computational power? Today, a handful of tech behemoths and chip manufacturers dominate AI compute. If UBC were implemented, either governments would have to build massive public compute clouds, or more likely, they would partner with or regulate private providers. Either scenario concentrates tremendous power at the production layer. Control the GPUs and servers, and you effectively control the mint for UBC tokens. As Mark Rydon noted, there’s skepticism whether incumbent cloud giants would even allow truly universal compute access, since it threatens their business model. Perhaps decentralized infrastructure (like blockchain-based DePIN networks) could break their hold, but at the end of the day, hardware and energy are finite resources. The entity (or cartel) managing production could potentially create artificial scarcity or set technical constraints that keep users in check. Much like OPEC can influence oil economies, a “Compute OPEC” could influence who gets how much computing and at what quality.

- Allocation Mechanisms: UBC might be “universal” in principle (everyone gets X tokens per month), but there will undoubtedly be policies for allocation. Perhaps unused compute credits expire (use it or lose it), or maybe people can trade them on an open market. If tradable, one can easily foresee wealthier actors buying up others’ UBC tokens – converting economic inequality into compute inequality. If non-tradable, black markets might appear. The rules of allocation (set by code or law) will determine whether UBC truly empowers individuals or becomes just another resource captured by the powerful. Moreover, any adaptive allocation (say, giving more compute to those deemed “high productivity” or cutting off those flagged for misuse) opens a Pandora’s box of algorithmic governance. We may see AI-driven rationing systems that dynamically adjust how much compute you get based on your behavior, similar to how some algorithms could ration other resources “fairly” but opaquely. The moment allocation isn’t strictly equal and unconditional, it becomes a tool for social engineering.

- Digital Identity and Rights: UBC cannot function without a robust digital identity system. After all, the system needs to ensure each person (each human existence) gets their share of compute and no more. This likely means every individual must be biometrically identified or otherwise verified – a prospect already being pursued by projects like Worldcoin, which scans irises to create a unique World ID for every person. In Altman’s vision, such an ID could distribute not just UBI funds but potentially UBC credits in the future. The catch is, you’d now have a globally recognized ID tied to all your digital transactions. If you thought surveillance was pervasive now, imagine every compute token you spend being attached to your identity in a ledger. Proponents claim the system can be private and secure (Worldcoin, for instance, insists it’s designing a privacy-preserving, decentralized ID network). But even if the tech is airtight, the existence of a single ID that gates your access to compute is a single point of failure for personal freedom. It is trivially easy under such a regime for authorities to punish an individual by revoking or suspending their ID, effectively freezing their UBC entitlements and by extension their ability to function in a digital society. We’ll discuss this enforcement explicitly in the next section – it is the ultimate trump card of control.

- Redefinition of Rights: The introduction of UBC would necessitate legally defining new rights and responsibilities. Is access to compute a right or a privilege? The Montana law cited earlier, for example, tries to preemptively frame access to computing as akin to freedom of speech. But other jurisdictions might go the opposite direction, viewing access to advanced AI as a privilege that can be revoked for “misuse.” Moreover, if one’s livelihood and basic needs are tied to UBC, compute access starts to look like a right to life. We might talk about a “right to algorithmic justice” or a “right to digital due process” – meaning, if you are to be cut off from compute, you deserve some due process. Otherwise, being cut off is tantamount to being exiled or imprisoned in a world where everything requires those digital tokens. New rights would also be needed to protect privacy (so that using your compute doesn’t automatically mean your data is siphoned) and to ensure neutrality (so that the infrastructure providers can’t discriminate or censor arbitrarily). Without strong constitutional-level protections, a UBC world skews heavily toward privileges granted by authority rather than inalienable rights. And privileges can be pulled at will.

In all these layers, we see the potential for agency to be stripped away. Agency – a person’s ability to make choices and act on their own will – is compromised if at each layer someone else holds the kill switch. You might “own” compute tokens, but if the hardware owner decides to prioritize other uses, your tokens might suddenly buy you half the compute they did last month (think of a landlord raising rent arbitrarily – now it’s a cloud landlord raising the price of flops). Or if the algorithmic allocator downgrades your status because an AI decided you’re “misusing” resources (maybe you were running too many encryption tasks, which it flags as suspicious), you have no recourse. If your digital ID is tied to everything, you cannot even seek an alternative provider – you are always already identified as the same person and subject to the same rules anywhere you go.

In summary, UBC doesn’t just create a new welfare benefit; it redefines the infrastructure of society. It recenters power in those who run the digital systems and effectively reengineers rights for the digital age – often not in citizens’ favor. To drive this home, let’s delve into what enforcement looks like in such a world. How might authorities or corporations ensure the UBC system “works as intended”? The answer is: by wielding the terrifying power of digital service revocation.

Policy by Blackout: Enforcement Through Digital Revocation

One of the most dystopian aspects of a UBC-driven society is how compliance could be enforced. In the old welfare state, if you broke rules, maybe your cash benefit was cut, or you faced a fine or jail – all unpleasant, but often requiring legal process. In a fully tokenized existence, punishment can be swift, automated, and granular: simply flip off the offender’s access to the digital grid. This is policy by blackout – enforce norms by threatening to digitally disappear someone.

We already have a glimpse of this future in China’s Social Credit System. Millions of “discredited” citizens have been banned from buying plane or train tickets, their travel rights nullified with a keystroke. The Chinese slogan explicitly says: “allow the trustworthy to roam everywhere under heaven while making it hard for the discredited to take a single step.” That phrase should send a chill down anyone’s spine. It is the ethos of digital totalitarianism: behave, or be virtually exiled. Social credit punishments have included barring people from public transportation, denying loans, and even publicly blacklisting individuals. This is all achieved by centrally coordinated data and digital control – you go to book a ticket, the system checks your ID against a blacklist, and deny: “access refused.” No court, no appeal (at least in many cases).

Now, transplant this capability into a UBC framework. Your UBC credits and digital ID are effectively your passport to participating in society. If an authority – be it the government or a corporate terms-of-service algorithm – decides you’ve violated some rule, it could revoke your credentials or reduce your allocation. For example, imagine a future law that says using your compute to generate deepfakes or hate speech results in a one-year suspension of UBC. That punishment would be devastating: it’s not just a fine, it’s a year-long exile from full participation in the economy. If all your appliances, communications, and work tools rely on spending compute credits, you’ll be left in the dark ages. Even if basics like food and shelter are guaranteed through other means, your capacity to do anything “beyond subsistence” is gone. In effect, it’s house arrest or worse – because at least in house arrest you have electricity and phone. Digital revocation would be a new form of civil death.

Corporate enforcers could do similarly for their domains. Picture the equivalent of being banned from Facebook or Twitter today, but in this future, being banned from the dominant compute network. We see shadows of this already: get banned by Amazon Web Services or Google Cloud for violating their policies, and your online business can evaporate overnight. In a UBC world, if your very personhood is tied to an account, getting banned by a platform could be tantamount to losing a limb. Perhaps there will be layers – maybe you only lose access to certain AI models if you break their specific rules. But even that could strongly shape behavior: if, say, misinforming people causes you to lose access to high-quality AI language models (effectively muzzling your ability to spread content), that is a deterrent (some might argue a welcome one in that narrow case!). But who defines “misinformation” or other transgressions? Likely the powers running the system.

We must reckon with the fact that digital systems allow extremely fine-grained and immediate control, far beyond analog precedents. A medieval lord could banish a peasant, but that took effort and was a blunt action. A UBC system could algorithmically downgrade or throttle you in realtime. Perhaps a troublesome dissident simply finds their AI assistant responds slower and with less useful info – a subtle form of ostracization. Or their smart home devices mysteriously revert to basic mode, making life less convenient. These kinds of digital sanctions could pressure individuals to conform without ever needing a public show of force.

This isn’t science fiction; it’s a logical extension of trends today. We already see western democracies flirting with powers to deplatform extremists, freeze protestors’ bank accounts (as happened to some involved in protests in recent years), or use spyware to monitor and neutralize activists. In a tokenized society, the more everything is tied into the system, the more a dissident stands out by attempting to exit or work offline – and the easier it is to bring them to heel by cutting their digital lifeline.

One could argue there will be appeal processes or protection against such abuse in well-run societies. Perhaps. But even the existence of this tool shifts the balance of power heavily. If a government agent or corporate algorithm can turn off your access with one command, the fear of that alone is enough to instill self-censorship and compliance. It’s the Panopticon effect: knowing you could be watched or cut off makes you behave. People may think twice about googling certain ideas or using their compute for controversial projects if they know it could flag them for scrutiny. The result is a chilling of innovation and expression – ironically the opposite of the supposed empowerment UBC was to provide.

To be very clear: the ultimate extractable resource in this system is you. Your compliance, your data, your very presence online – that is the product. UBC creates a mechanism to ensure you keep producing those outputs (because you must stay in the system to survive), and it provides an “off switch” to discipline anyone who doesn’t play their assigned role. In the darkest scenario, existence under UBC becomes contingent: a privilege granted by the system rather than an inherent right. You exist (socially and economically) only by virtue of the tokens and access bestowed on you. This is the trap: a gilded cage where the bars are made of code and policy, nearly invisible but unbreakable.

Erosion of Selfhood: Autonomy and Meaning in a Post-Labor World

Beyond these concrete power dynamics lies a more insidious consequence: the impact on selfhood and purpose. Work and agency have long been intertwined with identity – “you are what you do,” as the saying goes. In a world where 99% of traditional labor is automated, we face a crisis of purpose: what do humans do, and who are we, when machines do everything? This question predates UBC; futurists and philosophers have been mulling the “post-work society” for years. The optimistic vision is that freed from drudgery, people will engage in creative, community, or leisurely pursuits, redefining work to include caregiving, art, learning, and other intrinsically motivated activities. In fact, proponents of UBI often cite this emancipatory potential – that a basic income could decouple survival from jobs and let people find meaning beyond paycheck-defined roles.

However, UBC threatens to undercut even that post-work optimism. By making compute the new currency, it keeps individuals tethered to a system of production – a system now run by AIs. You might not have a boss, but you have an AI platform you depend on. The risk is that people become passive consumers of AI outputs rather than active agents crafting their destiny. Why learn a skill when your allotted AI can do it for you? Why create art from scratch when you can generate it with a simple prompt using your monthly compute quota? In theory, people could use AI as a tool to amplify their creativity and curiosity – but if the paradigm is “sit back and let the system serve you,” passivity is encouraged. The narrative clarity and moral seriousness that comes from struggling with real challenges could give way to a shallow existence of AI-mediated stimulation.

There is also the peril of homogenization of experience. If everyone is drawing on the same pool of AI models (because those are what the UBC credits give you access to), there is a temptation to trust the machine’s output over your own intuition. Over time, human skills may atrophy. We might become managers of our AI proxies, our days spent allocating tokens to get this or that task done, but not doing the task ourselves. Life could feel like one endless menu of choices (“what do I have the AI do next for me?”) without direct engagement. This raises existential questions: Will we feel purposeless? When work was the “cornerstone of identity, structure, and value exchange”, removing it without a satisfying substitute can lead to aimlessness or nihilism. Humans need to feel useful or at least meaningfully occupied. In a tokenized leisure dystopia, people may first revel in convenience but later flounder in existential dread, asking “What’s the point of me when the AIs do everything?”

Furthermore, autonomy suffers not just from external control, but from internal dependency. If you become so used to AI assistance for every little thing (because hey, you have these compute credits, might as well use them), you may lose confidence in your own abilities. This is similar to how over-reliance on GPS can erode your sense of direction. Here it’s over-reliance on AI for thinking and decision-making that can erode your mind’s independence. The freedom to think and decide for oneself could ironically be eroded by a policy born from the idea of “freeing” people from want. As we risk creating a generation of algorithmic wards, individuals who are technically free from labor but psychologically indentured to their digital nannies.

Even the concept of rights and citizenship could shift in unsettling ways. If one’s value is measured by how one uses one’s compute allocation, people might start optimizing themselves to please the system (to maybe get more credits or at least not lose them). Self-censorship and behavior modification, as discussed, can lead to a kind of split self: the authentic self vs. the performative, system-compliant self. Living under constant evaluation by an AI infrastructure (even if not overtly scored like China’s social credit, the mere fact that all your digital actions are observable can feel evaluative) can be corrosive to the human spirit. We might see a revival of Soviet-style double lives, where outwardly everyone toes the line (because the cost of deviation is high), while inwardly they feel hollow or resentful. Meaning and joy retreat into the shadows, as public life becomes a sanitized, token-mediated theater.

It’s worth considering whether meaning could be found in new forms under UBC. Perhaps people will band together in communal projects, using their compute shares collectively for scientific research, art, or local governance. That is a hopeful scenario – humans reclaiming agency by cooperatively directing the AIs for common good. But notice, that requires a social consciousness and solidarity that the very structure of UBC undercuts by default. The default is individual allocation, not collective; it’s transactional, not relational. We would need to actively build social frameworks on top of UBC to foster community and purpose – it won’t emerge automatically from a system designed around individual tokens. There is a real danger that absent such conscious efforts, UBC leads to an atomized society of isolated users, each locked in their personalized AI bubble, interacting through the mediation of platforms, with little genuine human-to-human dependence. And nothing erodes meaning more than isolation and lack of genuine connection.

In sum, the existential consequences of UBC amplify the structural ones. It’s not just that Big Brother might be watching or controlling – it’s that we might forget how to be fully human. Selfhood could be reduced to a data profile, autonomy traded for convenience, and the rich tapestry of human meaning-making ironed out into a flat digital routine. This is the ultimate trap: not only capturing our resources and rights, but capturing our hearts and minds, lulling us into a sense of progress even as the floor of our humanity is slowly pulled away.

Averting the Trap: Toward Structural Safeguards and Alternatives

The picture painted so far is grim. Does it mean UBC is inherently evil and should be abandoned? Or can it be implemented in a way that avoids these dystopian pitfalls? It’s a monumental challenge to do so, but acknowledging the risks is the first step. Here are some structural safeguards and alternative approaches that might avert the trap or offer a better path:

1. Truly Decentralize the Infrastructure: If UBC must happen, the compute grid behind it should not be in the hands of a few tech lords or a central government alone. This means investing in open, decentralized networks of computing – perhaps leveraging blockchain-based coordination or federated models. Projects in the decentralized physical infrastructure (DePIN) space aim to harness idle GPUs worldwide and avoid monopoly. A distributed ownership model (imagine every citizen also physically owns a micro-server or has stake in local compute co-ops) could prevent single-point control. It’s the difference between a peer-to-peer commons and a company town – the former empowers participants, the latter enriches a landlord. Decentralization won’t happen by accident; it needs policy support (incentives for open-source AI, anti-trust enforcement on cloud providers, perhaps publicly funded community clouds). The goal should be that revoking one’s access is not as simple as flipping one switch – no central authority should have kill-switch power over the entire network.

2. Protect Digital Rights in Law: We need a new Digital Bill of Rights to go alongside any UBC rollout. This would encode things like the right to digital self-determination, the right to privacy of one’s data and actions, the right to appeal algorithmic decisions, and perhaps most crucially, the right to not be excluded from the digital society without due process. If compute access is life-critical, disconnecting someone should require a legal procedure analogous to a trial. Montana’s Right to Compute Act is a start, ensuring individuals can use their own computing devices freely, but we need to broaden that. For instance, one could mandate that UBC credits are property of the individual, not a license that can be arbitrarily revoked. If treated as personal property or even a form of digital currency, you gain some legal protections (unlawful seizure, etc.). Internationally, perhaps the United Nations would declare access to computation a human right, just as it did for internet access. That might sound symbolic, but it sets a norm that cutting off someone’s compute is an egregious act.

3. Hybridize UBC with UBI and Basic Services: One way to reduce the closed-loop dependency is to not make UBC the only game in town. A safer approach might be a bundle of entitlements: a traditional UBI (cash) to ensure freedom of choice in the market, plus UBC (compute credits) to guarantee tech access, plus Universal Basic Services (UBS) like healthcare, housing, education, etc., provided publicly. This diversified approach prevents any one system from being a single point of failure. If, say, your compute credits are suspended for some reason, you wouldn’t starve or be homeless because those are covered by other means. And having cash UBI means you could seek alternative tech solutions outside the official UBC network if it’s important to you (like paying for a separate compute provider). Essentially, never put all your eggs of survival in one basket. Balanced, multiple safety nets provide resilience against exploitation by any single benefactor.

4. Design UBC as a Commons, Not a Scrip: There is a design question: will UBC be implemented as a token (currency-like) or as a service provision (like giving everyone access to a public library of compute)? If it’s tokenized and tradeable, it risks becoming scrip or a speculative asset. If it’s a service (like you’re entitled to run X amount of code on government cloud or use public AI endpoints), it might avoid some commodification. One could envision Compute Public Options – say, public data centers where anyone can run jobs up to their quota, governed transparently, with no profit motive. This would be more like a utility model. The danger of tokens is they invite markets and middlemen; a rights-based service model might be more citizen-centric. Additionally, building in interoperability and portability is key: your “stake in AI’s future” should not lock you to a single vendor’s ecosystem. Think of how phone numbers were made portable by law – similarly, compute credits or accounts could be portable across providers, to prevent lock-in.

5. Anonymity and Digital Cash Equivalents: To counter total surveillance, it could be possible to incorporate privacy-preserving technology into UBC. For example, use zero-knowledge proofs or blind signatures so that people can spend compute credits without revealing their identity for every transaction. This would mimic the privacy of cash. It’s admittedly tricky – providers need to prevent fraud (no double dipping) which identity usually solves, but cryptographers may devise creative solutions (some systems allow verification of uniqueness without revealing identity details). The aim would be to maintain some sphere of anonymity, so that not every activity is linked to your social credit file. This goes hand in hand with decentralized identity – perhaps using self-sovereign identity systems where you control your ID and only share what’s necessary. Worldcoin’s approach tries to be privacy-preserving (iris code without storing the iris image, etc.), but many remain skeptical. Constant independent oversight and improvement of these systems would be needed to ensure they don’t become leaky data dragnets.

6. Cultural and Educational Adaptation: We must prepare society for meaningful living without traditional work. This means culturally revaluing activities that are not tied to market productivity. Education systems should pivot to teaching resilience, creativity, ethics, and social skills – things that help people flourish in freedom, rather than just vocational training. If UBC frees time, that time could either be wasted on bread and circuses or channeled into renaissance. It will take deliberate effort (community programs, incentivizing civic engagement or creative endeavors) to make sure it’s the latter. For instance, local communities might decide to pool some of their compute to tackle local problems (like climate adaptation or supporting local arts) – effectively giving people a project and sense of agency beyond consumption. Policies can encourage that, maybe by matching compute grants for cooperative projects. The key safeguard here is to keep humans in the loop as decision-makers, not just beneficiaries. A society of idle beneficiaries is one bad day away from unrest or despair. A society of active participants, even if not “working” in the old sense, can maintain its psychological and moral health.

7. Checks and Balances on Revocation: If we assume some system of revoking access must exist (e.g. to stop an AI runaway misuse or serious crime), then implement strict checks and balances. Any revocation above a very temporary minimal level should require human review, multiple authority sign-offs, and an appeals process. There should also be tiers of sanctions: maybe someone abusive online loses access to certain social AI apps but not their entire compute allotment which also powers their home and car – proportionality matters. Borrow concepts from criminal justice: due process, innocent until proven guilty (no automated penalties without verification), transparency (you should know why you were sanctioned and how to rectify it). Perhaps even a digital ombudsman office can be established to handle complaints and protect users’ rights against the system.

Ultimately, the safest route may be to question whether we need UBC at all. Perhaps focusing on UBI and broad public service provision (like funding free or low-cost internet and devices for all) is a more straightforward way to ensure equity without inventing an entire tokenized economy of compute. Sam Altman’s idea that “owning part of the productivity” is better than money is intriguing, but one could achieve a similar outcome by taxing AI productivity (say a windfall tax on AI companies) and redistributing in plain dollars to people, who can then buy whatever compute or services they want. That would avoid creating a closed loop. In other words, maybe the progressive goal of empowering people in an AI era is best met by expanding human options (education, UBI, public tech access in libraries and schools) rather than by corralling everyone into one system.

We stand at a crossroads: down one path, the gleaming promise of Universal Basic Compute, and down the other, a more cautious, pluralistic approach to the post-labor future. The trap of UBC is not inevitable. It is a result of choices in design and governance. We can choose openness over enclosure, rights over privileges, and human-centric values over pure efficiency. Existence should never be reduced to a line in a ledger, tokenized and tradable. Our lives are more than the sum of transactions, more than data points to be mined. Any system that touches the core of existence must be accountable to the people, or it has no moral right to exist.

Conclusion

Universal Basic Compute is a seductively modern idea – who wouldn’t want a share of the AI revolution? It is framed as a birthright of the future, a way to ensure no one is left behind in the age of algorithms. But as we’ve explored, turning existence into a metered service carries dire risks. UBC, as currently imagined, could all too easily morph into a digital trap, a high-tech update of feudal dependency where power concentrates in those who run the machines and individuals become tenants on the land of AI.

The tokenization of existence is not a distant speculative threat; it’s the logical culmination of trends already underway – in surveillance capitalism’s monetization of life, in big tech’s platform empires, in governments’ creeping use of digital control. UBC would bind these threads into a tighter knot, hard to unravel once in place. We must approach it with eyes wide open. The very fact that UBC is discussed as inevitable or necessary in some circles should prompt us to ask: progress for whom? under whose terms? True progress would empower individuals on their own terms, not make them captive consumers of state or corporate provision.

Perhaps the greatest irony is that a policy born from a desire to free people (from poverty, from joblessness) can end up enslaving them in a new way. We cannot afford to be naive about the architecture of our freedoms. If we architect it poorly, even utopia can become a gilded cage.

In closing, let us insist that the value of a human life can never be fully expressed in tokens – be they dollars or compute credits. Any future that treats human existence as just another input or entitlement, stripped of dignity and agency, is a future unworthy of us. We stand at the edge of a new era. We can take the path where technology enriches human freedom, or the path where technology administrators extract value from every human breath. The time to choose – and to embed our choice in laws, code, and culture – is now. Let us choose wisely, lest we inadvertently build the trap that we won’t be able to escape.

Sources:

- Altman, Sam and others on UBC vs UBI

- Micha Anthenor Benoliel, Universal Basic Compute: Democratizing Access to Computing Power

- Zuboff, Shoshana on surveillance capitalism

- Reddit history of company scrip and dependence

- ADP/ReThinkQ, Coal Company Scrip, on exploitation of scrip systems

- Sarson Funds, Digital Feudalism article on tech lords and data serfs

- CoinDesk op-ed on UBC feasibility and tech monopolies

- Worldcoin/Business Insider on digital ID for UBI/UBC

- Guardian on China’s social credit travel bans

- Sustainability Directory on Post-Work Society and purpose

- Montana’s Right to Compute Act via Mountain States Policy

- RightToCompute.ai manifesto on computing and freedom

This essay is part of the research foundation for The Theory of Recursive Displacement — a unified framework examining how AI-driven automation reshapes labor markets, capital flows, governance structures, and human economic agency. Read the full theory for the complete analysis.

Ask questions about this content?

I'm here to help clarify anything