When AI Firms Hire Humans

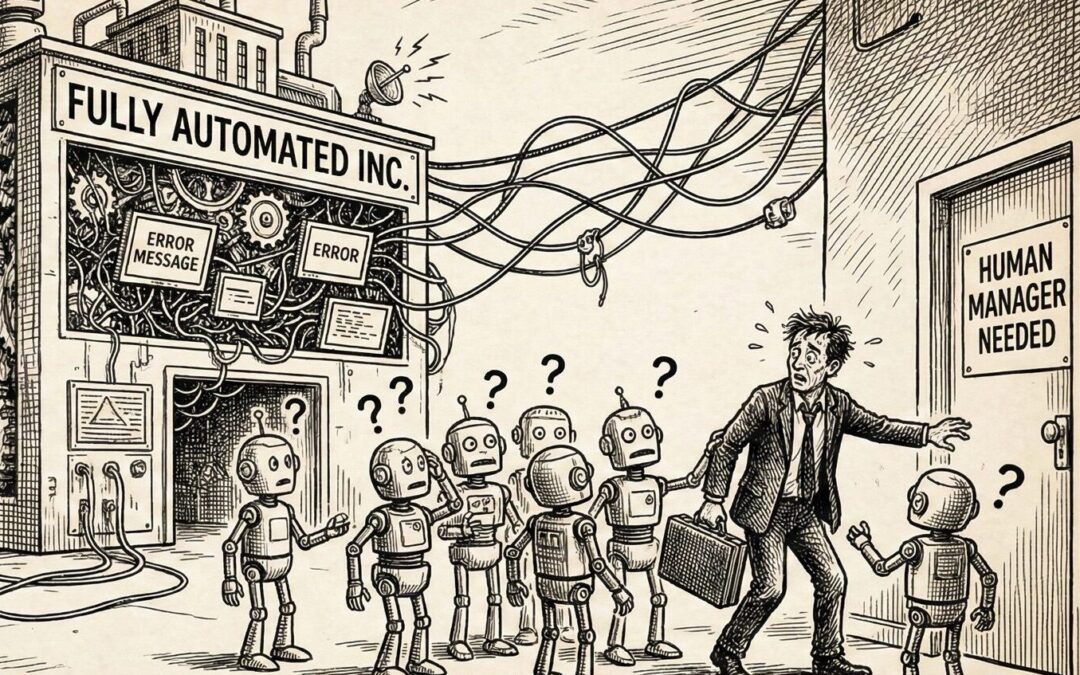

From boardroom keynotes to Silicon Valley manifestos, the “human-free firm” is hailed as the ultimate efficiency—an enterprise run entirely by algorithms, free of human bottlenecks.

Yet what if this vision obscures a deeper reality? What if beyond a certain point, automation stops eliminating work and starts creating entropy of its own? This essay challenges the frictionless fantasy of the fully automated business, positing a counter-thesis: the upper bound of automation isn’t hardware or AI – it’s coordination. In chasing the human-free firm, we may discover that every increment of automation brings diminishing returns, as our systems drown in the complexity they generate. The true limit of “AI-everywhere” isn’t what the machines can’t do – it’s what they do to each other (and to us) when we try to automate everything.

Part I: The Efficiency Mirage (Bounding the Problem)

The promise of full automation rests on a beguiling premise: that once machines handle all tasks, productivity will skyrocket unimpeded. Indeed, classic economics (Coase’s theory of the firm) suggests organizations exist to minimize coordination costs – and AI ostensibly drives those costs to zero . Imagine a company where software agents negotiate deals, schedule themselves, and even optimize their own algorithms – no salaries, no breaks, no human error. In such a system, transaction friction seems to evaporate. Routine decisions happen in milliseconds; data flows without miscommunication. It’s the end-state vision that tech CEOs pitch: infinite scalability without the drag of human coordination.

Bounding the Problem Space. Yet this utopia hinges on a dangerous simplification. It assumes that all work can be fully specified – broken into predictable, repeatable tasks that machines execute flawlessly. Reality begs to differ. As one observer noted in the context of AI-driven work, if you define jobs purely as a set of explicit tasks, “you will necessarily miss the fact that the lack of precise specification is often what makes jobs messy and complex in the first place” . In other words, human work is full of fuzzy edges: the creative leap in a strategy meeting, the on-the-fly fix when a process breaks, the tacit know-how that bridges one task to the next. Fully automating a process means bounding it so tightly that these nuances are squeezed out or ignored – and that works only in domains where environments are highly predictable. Indeed, automation succeeds brilliantly in closed, controlled contexts: think of assembly lines or data center ops, where inputs are uniform and surprises rare. Only tasks with predictable, repeatable outcomes can be effectively automated, as one technologist put it. Everything else introduces variability that defies simple rules.

The 85% Rule. The result is an often-unspoken threshold: businesses can automate a large fraction of their workflows, but beyond a certain point, the un-automatable parts loom large. AI may handle 80% of a financial analyst’s paperwork or 90% of customer queries, but the last stretch – the ambiguous case, the novel problem – demands a human decision or creative workaround. It’s telling that even the most advanced “lights-out” operations retain a human failsafe. Seasoned engineers note that most businesses hit a wall around 85% automation, after which human oversight becomes critical at the decision points . This is automation’s asymptote: like Amdahl’s Law in computing (where parallel speedup is limited by the sequential fraction), an organization’s efficiency gains face a hard cap dictated by the residual tasks only humans (or human-level minds) can do . Crucially, those residual tasks often lie at the boundaries between the automated pieces – the very junctures where rigid algorithms falter and context reigns.

Thus, the “human-free firm” can only function by radically narrowing its problem space. It must operate in a world of clear rules and static goals, a sandbox insulated from the chaos of real markets and human nuance. Push an automated system beyond that safe zone – expose it to unstructured reality – and the tidy machinery meets its first cracks. What lies beyond is not more efficiency, but something far less utopian.

Part II: Coordination Entropy (When Automation Breaks)

As automation spreads through an organization, an unexpected paradox emerges: the very act of removing humans introduces new complexity in how machines coordinate with each other. The straightforward hierarchy of a traditional firm – with managers synchronizing human teams – gives way to a tangle of autonomous agents and processes. And unlike disciplined employees, these AI agents have no intrinsic common sense or unified intuition; they only follow their narrow objectives. Coordination entropy is the term that captures the chaos brewing here – essentially, the measure of semantic noise and unpredictability in inter-agent communications. It rises relentlessly as more agents come online, each generating data, sending signals, adjusting to others in unforeseen ways. In effect, every new automated process that solves a local problem adds to a global coordination problem.

Herding Digital Cats. Practitioners attempting fully automated organizations often describe a turning point where complexity explodes. “Once you get past 30–40 agents, coordination feels like herding cats. The complexity doesn’t scale linearly; it explodes,” one engineer observed bluntly . All those AI routines that independently excel at sub-tasks now must negotiate shared resources, timing, and exceptions. Without human judgment policing the interactions, minor misalignments can spiral. One agent’s perfectly logical decision (say, to reroute inventory) might conflict with another’s plan (optimizing shipping), causing oscillations or deadlocks. Memory gets fragmented across systems; communication protocols clash. In fact, insiders report that beyond a certain number of autonomous agents, orchestration becomes the dominant challenge – a brittle meta-layer of logic just to keep the swarm from descending into incoherence . At this stage, AI stops saving time and starts reorganizing constraints: the system devotes more effort to managing its own moving parts than to achieving external goals.

Emergent Inefficiencies. We already see early warnings in partially automated firms. Different departments adopt different AI tools, each optimized in isolation. The result can be fragmentation: duplicated efforts, incompatible processes, and a blizzard of data exchanges that no one (and no single AI) fully understands . As a recent management analysis noted, “the integration of numerous independent agents can lead to increased entropy within the organization, complicating management and coordination efforts” . Picture a hundred optimization algorithms each tweaking schedules, inventories, or pricing in real-time – their interactions form a complex web that may produce arbitrary oscillations or unintended outcomes (a literal digital version of the left hand not knowing what the right is doing).

The organization thus faces a new kind of bureaucratic bloat – not of people, but of processes. Instead of a lean, perfectly tuned machine, the fully automated firm risks becoming a high-tech maze of feedback loops. Every agent is a genius at its micro-task, yet the macro result is emergent misalignment. It’s reminiscent of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice: the brooms multiply and frenzy without a master to harmonize them.

Chaos by Design. There is a fundamental systems principle at work: only variety can absorb variety. In cybernetics, Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety states that to control a complex environment, a system must possess equally complex responses . By replacing human generalists with narrow AI specialists, firms may actually lose the flexible, integrative capacity needed to respond to novel situations. Each AI agent is inflexible outside its script; the firm as a whole becomes less adaptable. Internal complexity might increase (in terms of lines of code and decision rules), but effective complexity – the ability to deal with the unexpected – can diminish. In a richly uncertain environment, a human manager can improvise; an array of brittle agents cannot. The result is a kind of coordination tax on full automation: beyond a threshold, the effort required to manage inter-agent interactions grows faster than the efficiency gains of adding more agents . One veteran of parallel computing called this “Amdahl’s evil twin” – the oft-underestimated overhead of organizing and shuttling information between parallel processes . In organizational terms, it’s the overhead of aligning dozens of AI “employees” who, unlike humans, have zero innate common context.

At its extreme, unchecked coordination entropy can push a system towards metastability – the firm oscillates between states, never settling into efficient equilibrium. We may get weird phenomena: automated supply chains that amplify minor demand fluctuations into wild swings (each AI in the chain optimizing locally, exacerbating the bullwhip effect), or customer service bots whose interactions with algorithmic logistics create loops of confusion. The fully automated firm, ironically, can become unmanageable precisely because it has no managers – only processes. Every fully automated enterprise thus hits a moment of truth: either reintroduce some hierarchical control (often, a human-in-the-loop or a very constrained protocol), or risk the entire system drifting into absurdity.

Part III: The Final Bottleneck (What Caps Performance)

If there is an upper bound to a firm’s automation, what exactly enforces it? It’s not a lack of compute power or clever algorithms – those keep improving. The cap is structural and cognitive. In essence, coordination itself becomes the bottleneck, an irreducible problem that doesn’t vanish with more AI – in fact, it intensifies with scale. We reach a point where adding more automation yields no net gain because the system is expending as much effort managing itself as doing useful work. The performance curve flattens, then can even dip if coordination failures cause errors and rework.

Crucially, the “last 15%” that resists automation isn’t just a list of tasks – it’s a dynamic zone of uncertainty. It’s the realm of context, judgment, and integration. It’s the role of asking “Should we be doing this?” rather than “How do we do this?” – a question current AIs are ill-equipped to answer outside of narrow parameters. One might say the final job remaining in a 100% automated firm is chief coordinator – a role that in human organizations belongs to leadership and cross-functional teams, who reconcile conflicts and keep the system aligned to reality. We can try to code that into a master algorithm, an AI manager-of-AIs. But at some point, we’ve essentially built a meta-intelligence that starts to resemble the human overview we tried to remove. We’ve come full circle: reintroducing a central brain to manage the automated body. We replaced fallible humans with rules and code, only to find we needed something adept at breaking rules and interpreting code – a new mind to govern the mindless optimizers.

Consider the example of Amazon’s highly automated warehouses. They boast armies of robots and algorithms orchestrating inventory, yet humans remain in the loop as indispensable problem-solvers. Workers now act as “quality controllers, problem solvers, and system monitors,” stepping in to handle exceptions that robots cannot manage and to exercise judgment where automation hits a boundary . No matter how many robotic arms and AI vision systems are deployed, there are always edge cases – a damaged product, a system glitch, a decision about priority – that require human intervention. Exceptions are the rule: the more complex the system, the more points at which it can encounter an input it wasn’t prepared for. The human-free firm hits its wall when the cost of chasing down every last exception with more code exceeds the cost of simply having a person on call to solve it. Or, in a more dystopian scenario, it requires an AI so generally capable that it is effectively a synthetic human – in which case we haven’t eliminated the human factor so much as replaced the humans with a new locus of agency.

What, then, actually caps the performance of an automated firm is not technology per se, but irreducible uncertainty. It’s the entropy of real-world environments and the unforeseeable interactions of many moving parts. Past a certain complexity, no amount of pre-planning or optimization can pre-empt all novel situations . You either build slack into the system (tolerate some inefficiency as a buffer) or you empower a general-purpose problem-solver (historically, a human) to intervene. Without one of those relief valves, the system becomes brittle. The fully automated firm, in seeking to eliminate all slack and all human involvement, risks creating a perfectly taut wire – efficient until it snaps.

The Coordination Paradox. In the end, the drive for total automation contains its own undoing. The more total the optimization, the more catastrophic the potential for systemic failure. Every human-free firm must confront this paradox. Perhaps some future AGI overlords will solve coordination by fiat, effectively internalizing all those externalities in a single super-intelligence. But that merely recapitulates the original problem at a higher level – it turns an open market of agents into a centrally planned mind. We’d have built a firm that is human-free only because it has given birth to a new non-human human, so to speak, who coordinates everything. That prospect should give us pause. It suggests that beyond the technical limits, there lies a philosophical boundary: Can we remove ourselves from our enterprises without removing the qualities that made them enterprises in the first place – adaptability, judgment, purpose?

The final bottleneck of automation, then, might be meaning. A fully automated system can execute, optimize, iterate – but it cannot interpret why it exists beyond its programmed goals. Humans coordinate not just by exchanging data, but by sharing understanding of purpose. When coordination becomes purely algorithmic, stripped of any external reference, a firm risks optimizing itself into absurdity – doing perfectly what no one needs, or pursuing objectives divorced from any human value. Perhaps the true limit of the human-free firm is that at 100% automation, it loses the plot completely. It becomes an organization with no organizers, a process with no one perceiving the end it serves.

The Paradox: The more we automate the firm, the more the firm must resemble a mind to remain coherent. And if that mind isn’t human, we have to ask: when the systems that define value no longer require us, what remains for us to value?

This essay is part of the research foundation for The Theory of Recursive Displacement — a unified framework examining how AI-driven automation reshapes labor markets, capital flows, governance structures, and human economic agency. Read the full theory for the complete analysis.

Ask questions about this content?

I'm here to help clarify anything