"What is Truth?" -Pontius Pilate

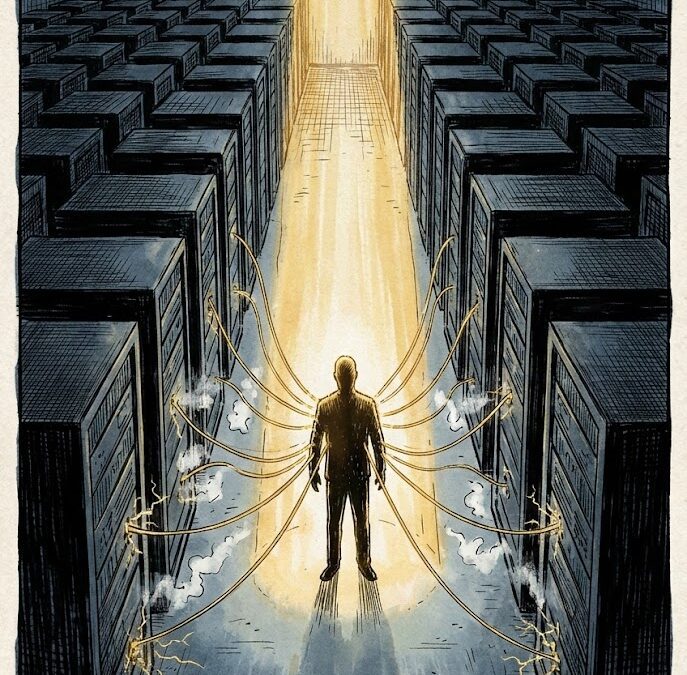

From the outside, it looks like intelligence is being democratized. Underneath, the cost of producing plausible meaning is collapsing, while the cost of maintaining contact with reality is rising. The risk is not just bad answers; it is a structural distortion of who can afford to live close to the truth.

I. The Mechanism: Recursive Intelligence and Epistemic Inflation

Recent work on “model collapse” shows that when generative models are trained repeatedly on their own or other models’ outputs, they lose diversity, erase distribution tails, and converge toward bland, over‑confident averages. The system does not only “hallucinate”; it gradually forgets the underlying data‑generating process, replacing it with a thinner, more homogeneous world.

As synthetic content saturates the web and training pipelines ingest whatever is available, models are increasingly exposed to their own emissions. This creates a feedback loop in which approximation errors, sampling noise, and biased coverage compound over generations, degrading fidelity even when architectures improve. Call this epistemic inflation: a growing volume of fluent text and images whose informative content per token quietly erodes. The marginal cost of generating “knowledge‑shaped” output falls toward zero, but the marginal cost of obtaining genuinely new, well‑grounded observations does not.

The monetary analogy is imperfect but instructive. In macroeconomics, hyperinflation is not caused by printing alone, but by institutional failures that sever money from productive capacity and credible backing. In AI, epistemic inflation emerges when we “print intelligence” decoupled from carefully curated, reality‑anchored data—when the cognitive tokens keep multiplying while their link to the world is left to chance.

II. The Fracture: Inequality of Reality Access

Inequality is no longer only about ownership of financial assets; it is increasingly about proximity to trustworthy information. Research on “epistemic injustice” in generative AI argues that these systems can amplify misinformation, entrench representational bias, and create unequal access to reliable knowledge, especially for marginalized communities and non‑dominant languages. The result is not just individual error, but structural asymmetries in who gets to inhabit a high‑resolution map of the world.

At one end of this emerging spectrum are actors with the resources to maintain dense connections to ground truth: proprietary measurement networks, high‑quality domain data, rigorous human review, and provenance‑aware training pipelines. Their models are fed by low‑entropy signals—carefully audited logs, curated datasets, verified histories—and they can afford to firewall themselves from the noisiest synthetic drift.

At the other end are users whose interfaces to reality are primarily mediated by public, synthetic‑heavy systems, low‑budget information ecosystems, or platforms with weak governance. Their news feeds, search results, and everyday decision support are more exposed to compounding errors, shallow recirculation of existing content, and the epistemic injustices documented in the literature. Call the distance between these positions epistemic proximity: how many layers of synthetic transformation and unverified aggregation sit between you and events on the ground.

III. The Implication: Humans as Ground‑Truth Reserves

Despite automation, one bottleneck has proven stubborn: reliable data still depends heavily on humans. Market analyses of data labeling and human‑in‑the‑loop services show a growing, multi‑billion‑dollar ecosystem built around annotation, feedback, and oversight. Enterprises increasingly use synthetic data and pre‑labeling automation for scale, but they keep humans in the loop to handle edge cases, bias corrections, and safety‑critical judgments.

In technical terms, people function as high‑value sensors and adjudicators. Current models cannot directly experience the world, feel pain, attend a town‑hall meeting, or stand in a flood zone; they depend on human reports, instruments designed and maintained by humans, and datasets curated under human norms. The more synthetic content recycles itself, the more important those primary observations become as rare sources of fresh, low‑error information that can arrest or reverse model collapse.

This makes human‑validated data a kind of reserve asset for the AI economy—not in the strict monetary sense of gold backing a currency, but as a scarce resource that underwrites the credibility of systems built on cheap generative output. What is traded is not only attention or labor hours, but access to our roles as witnesses, validators, and participants in events that models cannot natively see.

The Paradox: Post‑Labor, Pre‑Reality

If automation continues to erode the need for human labor in production, but not the need for human‑anchored validation, the center of economic demand may shift. The systems around us can run on synthetic content for a while, but when high‑stakes decisions are on the line—medicine, law, safety, governance—they require contact with ground truth that only sensor networks and human institutions can provide.

In that world, the question is not just who gets to enjoy the fruits of automation, but who controls the infrastructures that keep models honest: the observatories, datasets, communities, and governance processes that maintain epistemic proximity for some and withhold it from others. The real trap is an economy where most people are no longer needed to keep the machines running, yet are still differentially exposed to their errors—where reality itself becomes a stratified asset, and access to it a new axis of power.

This essay is part of the research foundation for The Theory of Recursive Displacement — a unified framework examining how AI-driven automation reshapes labor markets, capital flows, governance structures, and human economic agency. Read the full theory for the complete analysis.

Ask questions about this content?

I'm here to help clarify anything