A Serious Counter-Model: Why the Post-Labor Thesis Could Be Wrong

If the post-labor thesis fails, it will not fail because AI stalls, nor because capitalism suddenly becomes benevolent. It will fail in a more familiar way: by mistaking a fast-moving technological transition for a stable economic destination.

This essay constructs the strongest plausible counter-model to the post-labor thesis—not to dismiss its risks, but to test whether its core claims of inevitability, convergence, and structural displacement withstand sustained pressure. The alternative model argues that labor displacement is neither technologically predetermined nor economically dominant; that AI is more likely to reorganize work than eliminate it; and that institutions, demand, and political resistance remain strong enough to redirect outcomes away from the attractor states the thesis describes.

This is not optimism. It is a competing causal account.

1. Technological direction is endogenous, not fixed

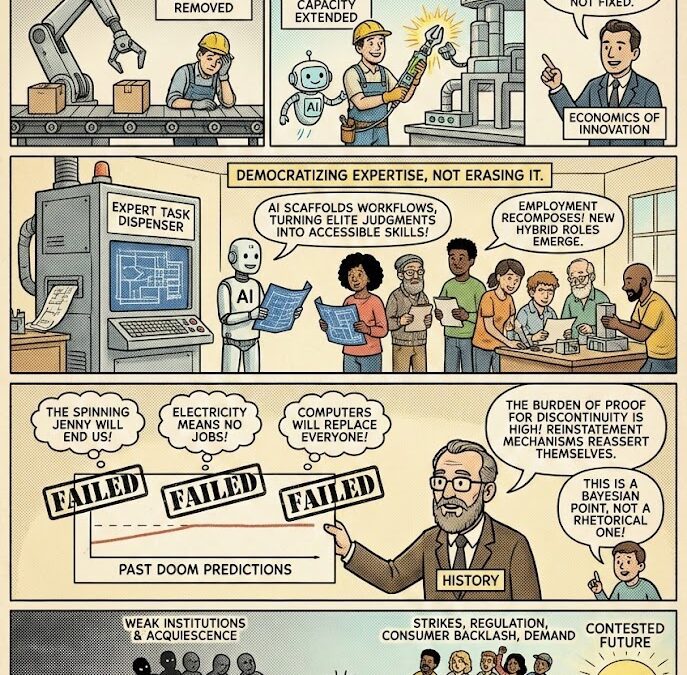

A quiet assumption beneath many post-labor arguments is that technological progress naturally trends toward labor replacement. But the economics of innovation does not support this. As the literature on directed technical change makes clear, the direction of technology responds to incentives, relative prices, market size, and institutional constraints.

Firms do not innovate in a vacuum. They innovate toward what is profitable under prevailing rules. When labor is cheap, unorganized, and weakly protected, labor-replacing technologies dominate. When labor is scarce, politically empowered, or legally embedded in accountability frameworks, labor-augmenting technologies become more attractive.

This distinction matters because AI is not a narrow technology with a single trajectory. It is a general platform that can be deployed in at least two directions:

- as an automation substrate that removes human inputs, or

- as an augmentation layer that extends human capacity, judgment, and throughput.

Which path dominates depends less on model capability than on deployment context. The post-labor thesis correctly describes one possible equilibrium under weak labor institutions and falling capital costs—but it often treats that equilibrium as a default rather than a contingent outcome.

In this counter-model, the “so-so technologies” critique becomes central: much automation is adopted not because it is optimal, but because it is locally cheap. Change the incentive gradient—through liability, regulation, consumer preference, or labor scarcity—and the direction of AI development can shift without any change in underlying capabilities.

2. AI may democratize expertise rather than erase it

One of the post-labor thesis’s blind spots is its treatment of expertise. It tends to assume that once a task becomes automatable, the labor associated with it disappears. But history suggests a more nuanced pattern: technologies often expand the population capable of performing high-value tasks by lowering skill barriers.

This is the logic behind expertise democratization. AI does not merely replace experts; it often turns what were once elite judgments into scaffolded workflows. When that happens, employment does not vanish—it recomposes.

This mechanism helps explain why early AI deployment often produces bifurcation rather than collapse. Junior roles that rely on unstructured learning pathways may shrink, while new hybrid roles emerge that combine partial expertise with AI support. In the medium run, this can expand service capacity rather than contract it—particularly in sectors with elastic demand like healthcare, education, compliance, and professional services.

The post-labor thesis sometimes assumes a fixed quantity of “knowledge work” to be divided between humans and machines. The counter-model rejects that premise. Productivity shocks historically expand markets as often as they compress labor input. Lower costs increase demand, throughput rises, and labor reorganizes around new bottlenecks.

This does not deny displacement. It challenges the claim that displacement dominates reinstatement at the system level.

3. The historical track record imposes Bayesian pressure

Predictions of permanent technological unemployment have an unusually poor track record. This is not a rhetorical point; it is a Bayesian one.

Each generation has produced confident forecasts that “this time is different.” Each time, the mechanisms of reinstatement—new task creation, demand expansion, institutional adaptation—reasserted themselves, often after painful transitions. The burden of proof for discontinuity is therefore high.

Methodological revisions over the past decade reinforce this caution. Occupation-level automation estimates consistently overstated risk by ignoring task heterogeneity and job recomposition. When those factors are included, predicted displacement falls sharply.

The post-labor thesis does not repeat these errors naively—but it does inherit their rhetorical posture. It often treats accelerating capability as sufficient evidence of accelerating displacement, even when aggregate labor outcomes remain stable. The longer that stability persists alongside rising AI adoption, the more explanatory weight the counter-model gains.

This does not refute the thesis. It forces it to explain why the historical mechanisms fail this time—not eventually, but decisively.

4. Labor share decline is real, but less deterministic than implied

The post-labor thesis places significant weight on the long-run decline in labor’s share of income. That decline is real. But its interpretation is contested in ways that matter for inevitability claims.

A substantial portion of the measured decline reflects accounting choices around self-employment income and depreciation. Net labor share behaves differently from gross share. Offshoring and globalization explain a non-trivial fraction of the trend, producing labor share compression without domestic automation.

Most importantly, recent data does not show monotonic acceleration. Volatility, partial rebounds, and cross-country divergence complicate the narrative of smooth convergence toward a single endpoint.

The counter-model does not require labor share to be rising today. It only requires that the decline not be uniquely attributable to automation, and not so structurally locked-in that institutional change is irrelevant. On that narrower claim, the evidence remains ambiguous.

5. “Attractor states” are contested equilibria, not defaults

The most philosophically vulnerable element of the post-labor thesis is its treatment of attractor states. These are described as outcomes that systems “naturally” converge toward under optimization pressure. But political economy rarely behaves that cleanly.

Attractor states require conditions:

- weak labor institutions,

- legitimacy of surveillance and control,

- enforceable identity infrastructure,

- economic justification that survives public scrutiny,

- and political exhaustion or acquiescence.

Those conditions are neither universal nor stable. They are contested. Strikes, regulation, consumer backlash, professional licensing, and procurement rules all impose friction on convergence.

The counter-model treats attractor states not as gravitational wells, but as failure modes—reachable under certain configurations, avoidable under others. That reframing does not deny risk. It denies inevitability.

6. The present data still leaves room for the counter-model

The counter-model’s strongest empirical anchor is simple: broad labor market collapse has not occurred.

That fact does not prove safety. It does, however, preserve multiple plausible trajectories. If displacement were already dominating reinstatement at scale, we would expect to see loosening labor markets, falling wages, and collapsing bargaining power. Instead, we see mixed signals: pipeline strain, yes—but also persistent demand, wage growth in some sectors, and political reactivation of labor.

The post-labor thesis can explain this through lag, measurement error, or hidden displacement. Those explanations are plausible—but they are not costless. Each year of stability increases the posterior probability that complementarity and absorption mechanisms are stronger than predicted.

7. What 2030 looks like if this counter-model is right

If the counter-model is broadly correct, the world of 2030 will not look “pre-AI.” It will look reorganized rather than hollowed out.

We would expect:

- redesigned entry-level pathways where AI scaffolds performance rather than replaces workers,

- expansion of mid-tier hybrid roles combining partial expertise with AI oversight,

- sectoral divergence where strong institutions capture productivity gains and weak ones do not,

- regulatory complementarity that keeps humans legally accountable in high-stakes domains,

- and visible natural experiments where institutional design, not technology, explains outcomes.

This is not utopia. It is a re-tiering of labor where humans remain economically central because systems are built to require them.

8. The real “kill shot,” properly stated

The strongest argument against the post-labor thesis is not that past doom predictions failed. It is that inevitability claims must defeat two adversaries at once:

- the historical tendency of economies to restore labor demand through new work, and

- the political capacity of societies to redirect incentives before convergence completes.

If the thesis cannot show why both mechanisms fail decisively—and on what timeline—then substantial uncertainty remains.

9. Honest assessment: how strong is this counter-model?

Where it is strong

- It correctly challenges inevitability framing.

- It grounds complementarity in incentive design, not hope.

- It fits aggregate labor stability better than collapse narratives.

- It treats institutions as causal variables.

Where it is weaker

- It may underweight the speed of capability unbundling.

- It assumes demand expansion outpaces substitution broadly.

- It assumes political capacity survives long enough to matter.

- It risks confusing “not yet” with “not happening.”

Calibrated conclusion

This counter-model deserves real probability mass—perhaps 20–35%—especially if entry-level pathways recover and AI diffusion continues without macro disruption. But it does not erase the risk surface identified by the post-labor thesis. Pipeline breakdowns, bargaining asymmetries, and transitional traps remain serious concerns.

The correct posture is not belief or disbelief, but disciplined uncertainty. The value of this counter-model is not that it proves the thesis wrong—but that it shows the future is still contested.

And in political economy, contestation is the opposite of inevitability.

Ask questions about this content?

I'm here to help clarify anything