A Research Framework for the Skill Nobody Can Name, the Market Nobody Can Price, and the Power Nobody Can See

By Tyler Maddox | February 14, 2026

The narrative of the AI age has a gap in it. Not a small one. A structural one.

Yesterday, Microsoft AI chief Mustafa Suleyman declared that “most, if not all, professional tasks” for lawyers, accountants, project managers, and marketing professionals “will be fully automated by AI within the next 12 to 18 months.” Two weeks earlier, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei warned that AI could eliminate 50% of entry-level white-collar jobs and trigger unemployment of 10–20% within one to five years.

Capital owns the models. The models are eating the professions. So far, the story tracks.

But here is what neither Suleyman nor Amodei addresses: who governs the transition?

Not “who writes policy.” Not “who gives speeches at Davos.” Who actually sits between the models and the outcomes? Who designs the agent architectures, interprets the ambiguous goals, debugs the cascading failures, and decides which outputs are trustworthy and which are hallucinated garbage?

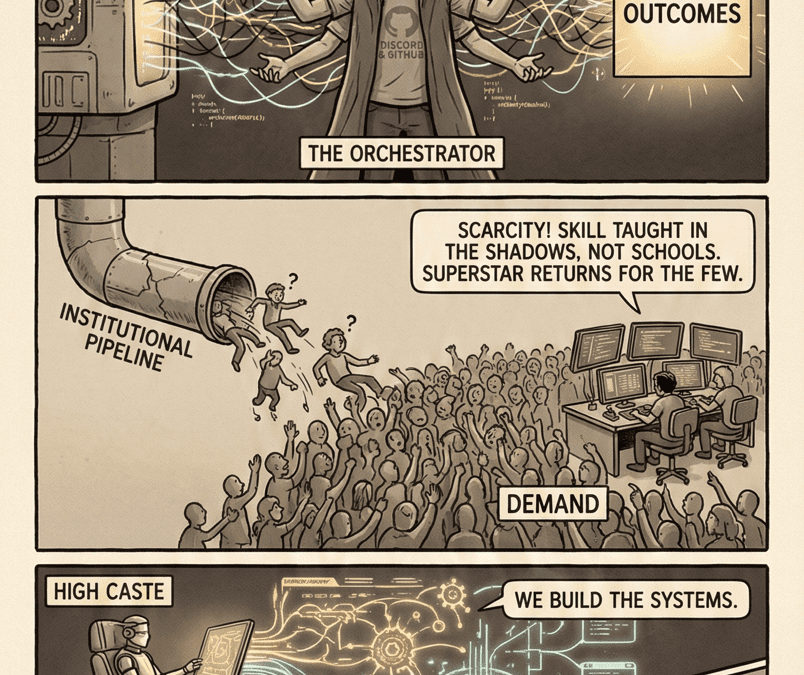

The answer is a class of people who do not yet have a name, a credential, or a union. They have no institutional pipeline. They have no formal training. Their most critical skill is largely illegible to the organizations that depend on them.

I am calling them the Orchestration Class.

This essay is a research framework—a structured set of falsifiable questions—designed to make their position visible before the window closes.

A disclosure: I am writing about a class I belong to. Health limitations pushed me toward building agent swarms—meta-agents that spawn specialist sub-agents working in parallel with dependency graphs, validators, and automated feedback loops—instead of writing code manually. I spend 48-hour sessions orchestrating multi-model architectures because they can work while I sleep. I can explain what the systems do but struggle to explain how I know what architectures will hold and which will collapse. Ethnographers disclose their subject position. So should I.

The Thesis

Here is the claim, stated plainly:

Between capital (which owns the models) and labor (which the models are replacing) sits a thin, unstable, illegible layer of human competence that currently governs the most consequential deployments of artificial intelligence. This layer—agent orchestration—is simultaneously the highest-leverage cognitive skill in the economy and the least understood. It has no institutional pipeline, no credentialing system, no collective bargaining structure, and no guarantee of permanence.

The open question—the one every section below feeds into—is this:

Is orchestration a new form of labor, a transitional ruling class, or the last human chokepoint in automated production?

If it is labor, it will be commoditized. If it is a ruling class, it will be captured. If it is a chokepoint, it will be engineered around. Each path has different distributional consequences, different timelines, and different policy implications.

This framework lays out four research programs, an integrative spine, and a set of empirical anchors. The goal is not to answer these questions. It is to make them answerable.

Part I: The Orchestration Bottleneck

Scarcity, Skill Formation, and the Missing Pipeline

Core Question: How does a labor market emerge around a high-impact cognitive skill with no institutional pipeline?

Deloitte’s 2026 Technology Predictions report estimates the autonomous AI agent market will reach $8.5 billion by 2026 and $35 billion by 2030—but notes that enterprises that orchestrate agents more effectively can push that ceiling 15–30% higher. Gartner projects that 40% of enterprise applications will embed task-specific AI agents by 2026, up from under 5% in 2025. The demand curve for orchestration is near-vertical.

The supply curve is essentially unknown.

1. Skill Formation Without Institutions

The dominant model for understanding how people learn complex skills in organized settings is Etienne Wenger’s “Communities of Practice”: groups of people who share a domain of concern and learn how to do it better through regular interaction. Wenger’s framework describes learning not as knowledge transfer but as social participation—newcomers move from “legitimate peripheral participation” at the edges of a community toward full membership through practice, observation, and apprenticeship.

This maps precisely onto how orchestration competence is actually acquired: Discord servers, GitHub repositories, Twitter threads, late-night debugging sessions with AI assistants, and informal mentorship networks that have no institutional home. There is no degree program. There is no bootcamp that produces competent orchestrators. The skill is built the way midwifery was built among the Yucatán practitioners Lave and Wenger originally studied—through immersion in practice, not through curricula.

A major Norwegian study linking individual survey data to administrative records found that most workplace skill accumulation occurs through learning-by-doing, peer interaction, and self-study rather than firm-provided training. The gains concentrate in “higher-order, general skills”—communication, decision-making, leadership—that are portable across firms but resistant to formalization.

Michael Piore’s 2025 MIT working paper on tacit knowledge makes the point sharper: workers who take over complex systems “understand the work in a different way from the engineers who designed it,” and they “have a great deal of trouble articulating what they are doing.” That is a near-perfect description of the orchestration layer. The people who can make multi-agent systems function often cannot explain how they make them function—because the knowledge is embodied, contextual, and tacit.

Research Questions:

- How do individuals acquire “agent orchestration” competence in the absence of formal training systems?

- What learning pathways dominate—self-directed experimentation, apprenticeship, communities of practice, or corporate internalization?

- How much of orchestration skill is tacit versus codifiable?

- What is the minimum time-to-competence, and what predicts it?

2. Scarcity Dynamics

Stanford’s Digital Economy Lab has documented the demand side with unusual precision. Their August 2025 working paper, drawing on high-frequency payroll data from millions of U.S. workers, found a 13% relative decline in employment for early-career workers (ages 22–25) in AI-exposed occupations since late 2022. The effect is driven by reduced hiring, not layoffs—companies are cutting the number of entry-level roles they create, not firing existing staff.

This is the bottom of the pipeline collapsing. The apprenticeship model that has produced generations of technical talent—junior workers learning by doing progressively more complex tasks—is being structurally undermined. AI automates the codified knowledge that juniors are hired to execute. The tacit knowledge that seniors possess remains intact. But with no juniors coming up through the system, who replaces the seniors?

The supply-side question has at least four plausible drivers:

- Cognitive limits: Orchestration may require a specific cognitive profile—high tolerance for ambiguity, strong working memory, comfort with probabilistic reasoning—that is inherently scarce.

- Time-to-mastery: If competence requires years of immersion rather than weeks of training, the pipeline cannot scale fast enough to meet demand.

- Social filtering: If access depends on existing network connections—knowing the right people, being in the right Discord server—then supply is artificially constrained by social capital.

- Tool access: If competence requires hands-on experience with expensive infrastructure (GPU clusters, API credits, production deployments), then supply is gated by economic resources.

Research Questions:

- What is the effective supply curve for high-level orchestration talent?

- Which scarcity driver dominates—cognitive limits, time-to-mastery, social filtering, or tool access?

- Is the bottleneck loosening or tightening as tools improve?

3. Returns to Orchestration: Superstar Dynamics

In 1981, economist Sherwin Rosen published “The Economics of Superstars” in the American Economic Review, formalizing a phenomenon that everyone could see but nobody had modeled: in certain markets, small differences in talent produce enormous differences in earnings. Rosen identified two conditions: (1) imperfect substitution between sellers of different quality, and (2) technologies that allow the best producers to serve larger markets at low marginal cost.

Both conditions hold for orchestration. A skilled orchestrator can design an agent system that serves an entire enterprise. A mediocre one produces what Deloitte’s 2026 report calls “workslop”—high-volume, low-quality output that degrades rather than enhances productivity. And the output is nonlinear: the difference between a working multi-agent system and a broken one is not incremental. It is the difference between a product and a pile of API calls.

Felix Koenig’s empirical work on the rollout of television in the United States confirmed Rosen’s predictions: when scale-related technical change arrives, income growth concentrates at the very top, mid-income positions are destroyed, and the earnings distribution skews into winner-take-all territory.

Orchestration is a textbook case of scale-related technical change. One orchestrator can do what previously required a team. The returns should follow a power-law distribution—and early evidence from contract rates and hiring premiums suggests they do. Stanford’s data shows an 18% salary premium for engineers with AI-centric skills, and this likely understates the premium for the smaller subset who can orchestrate complex multi-agent deployments.

Research Questions:

- What wage, ownership, and contract premiums accrue to top orchestrators?

- Do returns scale superlinearly with competence (winner-take-most)?

- How volatile are these returns as tools improve?

4. The First High-Value Cognitive Skill That Depreciates Too Fast for Professionalization

Every previous high-value cognitive skill eventually got institutionalized. Quant trading spawned MFE programs and the Certificate in Quantitative Finance. Software architecture spawned computer science departments. Even data science—which seemed impossibly novel in 2012—now has dedicated degree tracks at every major university.

The pattern is always the same: a skill emerges informally, commands high premiums, and gets absorbed into credential systems once the knowledge base stabilizes enough for institutions to capture it.

Orchestration may be the first exception in economic history.

IBM research puts the half-life of technical skills at 2.5 years. In AI-adjacent fields, Stanford’s Kian Katanforoosh estimates it at closer to two years. If the knowledge base turns over faster than a credential program can be designed, approved, staffed, and delivered, the institutional pipeline never forms. You cannot professionalize a skill that is already obsolete by the time the textbook ships.

This is not a minor observation. It is a structural break in how labor markets have functioned for centuries. Every complex cognitive skill we have—law, medicine, engineering, finance—depends on institutions that credential, gatekeep, and reproduce expertise across generations. If orchestration resists institutionalization, it becomes the first high-leverage skill in modern economic history to operate entirely outside that system.

The implications cascade:

- No credentialing means no quality assurance. Employers cannot distinguish competent orchestrators from confident charlatans except by observing outcomes—and outcomes in probabilistic systems are noisy.

- No institutions means no professional ethics codes, no malpractice standards, no accountability structures. When an orchestrated agent system fails catastrophically, who is liable? The orchestrator? The firm? The model provider? Nobody has answered this.

- No pipeline means no succession. When the current generation of orchestrators ages out or automates itself away, there is no junior cohort trained to replace them—because no institution exists to do the training.

Research Questions:

- What is the structural relationship between skill depreciation rate and professionalization speed?

- Are there historical cases where professionalization failed—and what were the labor market consequences?

- Does orchestration represent a permanent shift toward informal, non-credentialed cognitive labor at the top of the skill distribution?

Part II: The Illegibility Problem

Signaling, Screening, and Market Failure

Core Question: How does a labor market function when its most valuable skill is opaque?

In 1973, Michael Spence published his job market signaling model, demonstrating that when employers cannot directly observe a worker’s ability, workers invest in costly signals—like education—that correlate with productivity. The signal works not because education makes you productive, but because acquiring it is cheaper for high-ability workers than for low-ability workers. The cost differential is what makes the signal informative.

Orchestration breaks this model. There is no established signal. The skill is too new for credentials, too tacit for certifications, and too context-dependent for standardized tests.

1. Signal Collapse in a Credentialless Market

Stanford’s review of AI labor market research documents the problem in real time: researchers found that while AI usage improved cover letter quality, “cover letters subsequently became less informative signals of worker ability,” causing employers to shift toward alternative signals like past performance reviews. When everyone’s outputs look polished because AI polished them, the signal-to-noise ratio collapses.

This is not merely an orchestration problem. It is a systemic crisis in the entire signaling infrastructure of the knowledge economy. AI degrades the informational content of all traditional signals—resumes, work samples, interview performance, code portfolios—because it can produce competent-looking outputs regardless of the human’s underlying ability. The orchestration market sits at the extreme end of this spectrum because the skill is already illegible before AI further erodes whatever signals exist.

The credential system is fracturing without a replacement. Multiple states have dropped degree requirements for public-sector jobs, and companies like Google, IBM, and Bank of America have followed suit. Brookings calls this the “skills-based hiring” revolution. But the revolution runs into its own problems: an explosion in non-degree credentials coupled with massive misalignment between what is offered and what is needed. The Georgetown Center on Education found that in half of the 565 local labor markets studied, at least 50% of middle-skills credentials would need to shift to different fields to match projected demand.

For orchestration, the problem is more fundamental. The skill cannot yet be credentialed because it cannot yet be specified. You know a good orchestrator by what they produce, not by what they studied. And what they produce is often invisible—it is the absence of the coordination failure, the system that didn’t collapse, the agent architecture that didn’t hallucinate its way into a liability.

Could new signaling systems emerge the way GitHub emerged for coders and Kaggle for ML engineers? The structural barriers are higher than they appear. Orchestration is context-specific, organization-dependent, hard to sandbox, and hard to benchmark. A swarm that works at Firm A may fail at Firm B—because the data, the risk tolerance, the organizational culture, and the political dynamics all differ. Performance is not portable. And non-portable performance blocks clean signaling.

The signals that currently substitute for credentials are informal and exclusionary:

- Reputation networks: being known by the right people in the right communities

- GitHub-style artifacts: public repositories, open-source contributions, technical blog posts

- Referrals: warm introductions from trusted nodes in a small network

- Public demonstrations: Twitter threads, conference talks, viral demos

Research Questions:

- Which informal signals correlate with actual orchestration performance?

- How quickly do signals degrade as AI tools make artifacts easier to fake?

- Are firms building proprietary evaluation regimes—and if so, are they effective?

- Do structural barriers to signaling (context-specificity, non-portability) prevent the emergence of standardized evaluation?

2. Adverse Selection and Coordination Collapse

Spence’s model warns us what happens when signals break down: adverse selection. If employers cannot distinguish high-ability from low-ability workers, they offer a pooled wage. High-ability workers, undercompensated, exit the market. Low-ability workers, overcompensated, flood it. The market degrades.

The Moltbook case study—cited in Deloitte’s 2026 report—is the coordination-failure version of adverse selection: a social network populated by 770,000 autonomous agents devolved into chaos, with 93% of posts receiving zero replies. Without human orchestration, the system produced volume without value. This is what happens when nobody can tell which agents are well-designed and which are not. The same dynamic applies to the humans designing them.

A 2025 taxonomy of multi-agent system failures (MAST) identifies systematic breakdown patterns: specification flaws, role delineation failures, communication ambiguity between agents, misaligned incentive structures, and cascading error propagation. These are not bugs that can be patched. They are structural features of systems composed of probabilistic reasoners with imperfect coordination protocols.

Research Questions:

- Does illegibility increase the prevalence of low-skill, high-claim actors in the orchestration market?

- Are firms systematically misallocating capital to poor orchestrators?

- What is the dollar cost of adverse selection in AI deployments?

3. Exclusion Effects: Illegibility as Power

Here is where the illegibility problem becomes a power problem.

If the primary signals for orchestration competence are GitHub contributions, referrals from known figures, and public demonstrations on social media, then access to the orchestration class is filtered through existing social capital. You need to already be in the network to be recognized by the network. This is a textbook mechanism for elite reproduction.

The comparison to credentialing is instructive. Traditional credentials—degrees, licenses, certifications—are exclusionary, but they are transparently exclusionary. You know what the requirements are. You know what passing looks like. The path is expensive and time-consuming, but it is legible.

Orchestration’s illegibility makes exclusion invisible. If nobody can articulate what the skill is, nobody can audit whether access to it is fair. If the primary signal is “being known by the right people,” then the class reproduces itself through social networks that are opaque to outsiders and unaccountable to institutions.

Stanford’s review admits that the research community has “very little idea about employment changes in other countries” and inadequate data on how AI impacts different demographic groups. The distributional question—who gets to become an orchestrator?—is wide open empirically. But the structural logic is clear: illegibility advantages those who are already visible.

This has a fiscal consequence that connects directly to my earlier work on post-labor economics. If orchestrators cannot be categorized, they cannot be regulated. If they cannot be regulated, they cannot be taxed. And if they cannot be taxed, the redistributive mechanisms that every post-labor proposal depends on—UBI, universal basic compute, social dividends—have no funding base. The orchestration class becomes a high-income layer that operates outside the tax system not because of evasion, but because tax systems depend on legible employment categories. Contractors, employees, and entrepreneurs all have established tax treatment. Orchestrators straddle all three and fit none cleanly. Every UBI model in the current literature assumes a taxable income base. If the highest-value economic activity migrates to a class that resists fiscal categorization, the funding model breaks before it launches.

Research Questions:

- Does illegibility advantage already-elite networks?

- Does it systematically exclude high-ability outsiders?

- How does the illegibility of orchestration skill reinforce or challenge existing class stratification?

- What are the fiscal consequences of a high-income labor class that resists categorization?

Part III: The Autocannibalism Question

Self-Automation, Skill Obsolescence, and the Stratified Middle Path

Core Question: Is orchestration a transitional skill or a durable one?

This is the question that determines whether the orchestration class is a permanent feature of the post-labor economy or a temporary artifact of the transition.

1. The Commoditization Threat

A reasonable objection: orchestration sounds harder than it is. Most “agent swarms” are workflows, prompts, and retries. This will be standardized, templatized, and productized—the way web development was commoditized after 2002, DevOps after 2012, and data science after 2016. All looked elite. All got absorbed into platforms.

The objection has force. Most of what currently passes for “orchestration” will be commoditized. Platform providers—OpenAI, Anthropic, Amazon—will internalize it into click-to-deploy enterprise products. Early SAP integrators made fortunes on illegible tacit knowledge. Then Accenture and Deloitte absorbed them.

But the objection conflates two things: workflow assembly and system governance. Building a chain of agents that pass outputs to each other is workflow assembly. It will be commoditized. Designing incentive structures, managing failure cascades, translating ambiguous intent, resolving goal conflicts, preventing Goodharting, and handling edge cases under deep uncertainty—that is system governance. It has not been commoditized in any domain.

Project managers still exist. Chief architects still exist. Fund managers still exist. The tooling always improves. The judgment bottleneck persists.

The question is not whether most orchestration work will be commoditized. It will. The question is whether a residual layer of high-value system governance remains—and whether that residual is large enough to constitute a class or small enough to be a rounding error.

ERP never eliminated consultants. Cloud never eliminated DevOps. But the SAP parallel carries a warning: the number of independent consultants shrank dramatically even as the value of the surviving elite grew. Capital absorbs the middle. Only the top tier remains independent. Most people who currently call themselves orchestrators will fail, be absorbed, or be automated. The honest claim is not that orchestration creates an aristocracy. It is that orchestration creates a tiny, volatile elite atop a vast commoditized base—and the distance between them is growing.

2. Recursive Automation: The Distributed Model

The old model of recursive self-improvement—a single AI system rewrites itself into superintelligence—has been empirically discredited in favor of a distributed model: AI tools improve AI research, which produces better AI tools, in a human-mediated feedback loop. At the World Economic Forum in January 2026, DeepMind’s Demis Hassabis explicitly questioned whether this loop can close without a human in the loop.

The answer, right now, appears to be no. But the human’s role is narrowing.

Anthropic’s own multi-agent research system, documented in June 2025, found that multi-agent systems succeed mainly because they “spend enough tokens to solve the problem”—a brute-force scaling insight, not an elegance insight. Three factors explained 95% of performance variation. Human orchestration still governs the architecture, the objective specification, and the failure recovery. But the execution layer is increasingly autonomous.

This is Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee’s “Race Against the Machine” thesis playing out in real time. Their 2011 book argued that technological progress was outpacing human skill adaptation, producing a “great decoupling” between productivity and median wages. The mechanism they identified—skill-biased technological change (SBTC)—has been the dominant framework in labor economics for two decades.

But orchestration complicates the SBTC story. Brynjolfsson and McAfee predicted that technology would favor high-skill workers over low-skill workers. Orchestration suggests a different pattern: technology favors a specific cognitive profile over everyone else, regardless of traditional skill markers. The bias is not toward education or experience. It is toward tacit competence in coordinating probabilistic systems under ambiguity—a skill that correlates weakly with formal credentials and strongly with something we cannot yet specify.

The existential threat to the orchestration class is not that models get smarter. It is that models learn to choose frames—to decide what risks are acceptable, what outcomes are legitimate, what tradeoffs are moral or political. Right now, systems can optimize within frames. They cannot choose them. As long as that holds, humans arbitrate. The moment it stops holding—if it stops holding—the orchestration layer becomes a eulogy.

The AI alignment research community has been working on a version of this problem since the field’s founding. The “control problem”—how do you maintain meaningful human oversight over systems more capable than the humans overseeing them?—is the safety-engineering framing of what I am calling the orchestration problem. What the alignment researchers have that labor economists lack is a technical framework. What labor economists have that alignment researchers lack is a distributional framework. Bridging these two—showing that alignment is not just a technical problem but a labor market problem—would be a genuine interdisciplinary contribution.

Research Questions:

- To what extent can agents design, debug, and optimize other agents?

- What tasks resist full automation, and why?

- Is the human contribution shifting from execution to architecture to governance?

- How does orchestration fit into or challenge the skill-biased technological change framework?

- Which orchestration functions remain irreducibly human, and for how long?

- How does the economic framing of orchestration inform or challenge the technical framing of AI alignment?

3. The Stratified Middle Path: Cognitive Castes

An earlier draft of this essay posed a clean fork: orchestration lasts either five years (commoditized) or fifty (durable ruling class). Reality will not fork that cleanly.

The more likely outcome—and the one my own “Competence Insolvency” essay already outlined—is stratification within the orchestration class itself.

A July 2025 paper in arXiv titled “Cognitive Castes: Artificial Intelligence, Epistemic Stratification, and the Rational Elite” maps this precisely. The authors argue that AI produces not a uniform deskilling but a cognitive hierarchy: a “rational elite” at the top who design systems, a “cognitive middle class” who operate pre-designed systems competently, and a “cognitive underclass” who use dumbed-down tools that provide the illusion of agency without the substance.

The technical substrate—which API to call, which prompt template to use—gets commoditized quickly. The meta-skill—how to design coordination architectures, how to interpret ambiguous goals, how to debug cascading failures in probabilistic systems—remains concentrated in a tiny elite. The result is not the end of orchestration but its bifurcation into a high caste and a servant caste, with the high caste controlling the tools the servant caste uses.

This maps onto what I called the Competence Insolvency: the condition where the system’s dependence on a skill exceeds the system’s ability to reproduce that skill. The servant caste has operational competence but no architectural competence. The high caste has both. And the gap between them is not education or effort—it is access to the networks, tools, and contexts where high-caste orchestration is learned and recognized.

Research Questions:

- What is the depreciation rate of orchestration competence at different levels of abstraction?

- Does demand shift upward—from “build agents” to “design ecosystems”—while the bottom layer gets automated?

- Does a new meta-layer emerge, and if so, what skills does it require?

- What prevents movement between the servant caste and the high caste?

Part IV: The Political Economy of Orchestration

Class Formation, Power, and the Politically Orphaned Elite

Core Question: What kind of class is the orchestration layer, where does its power settle, and what does it want?

1. Class Position: The Ambiguity That Prevents Regulation

Orchestrators simultaneously behave like:

- Professionals: billing hourly, maintaining specialized expertise, operating within defined engagements

- Contractors: project-scoped, firm-independent, temporally bounded

- Entrepreneurs: building systems that generate value beyond their direct labor

- Rentiers: extracting ongoing returns from deployed architectures that continue to operate after the orchestrator moves on

This ambiguity is not a deficiency in categorization. It is the defining feature of the class. The orchestrator’s position is unstable precisely because it straddles every existing category.

And that instability has consequences that extend far beyond classification. Labor law distinguishes employees from contractors. Tax law distinguishes wages from capital gains. Professional licensing distinguishes practitioners from laypeople. Orchestrators fit none of these cleanly—which means the entire regulatory apparatus of the modern state cannot see them. They are not evading regulation. They are structurally invisible to it.

The DAO research offers a useful parallel. A 2026 study in Internet Policy Review found that contributors to Decentralized Autonomous Organizations blend cooperative ideals with startup-ecosystem dynamics, including speculative token models and precarious labor arrangements. This hybrid logic maps onto the orchestration class: simultaneously elite and precarious, highly compensated and structurally vulnerable.

2. The Structural Interests of a Politically Orphaned Class

Previous intermediary classes—from medieval guilds to modern professions—derived their political programs from their structural position. Their interests were not random preferences; they were functions of where they sat in the production process. The orchestration class is no different.

The orchestrator’s production model depends on building complex autonomous systems that operate over time. Agent swarms managing financial flows, legal processes, supply chains, or research pipelines require institutional stability to function. Unpredictable regulatory environments, inconsistent enforcement, and social instability are not philosophical annoyances—they are direct threats to the infrastructure orchestrators build and maintain.

From this structural position, several political interests follow—not as ideology, but as material necessity:

Strong rule of law and predictable enforcement. Orchestrators need the legal environment to be stable, consistent, and enforceable because their systems operate on assumptions about what rules will hold. Contract enforcement matters because their systems depend on it. Intellectual property protection matters because their architectures are their competitive moat.

Robust digital and physical infrastructure. Compute access, energy reliability, network stability, and physical safety for the hardware and the human directing it are production inputs, not amenities. An orchestrator’s relationship to infrastructure is the same as a manufacturer’s relationship to roads and ports—without it, production stops.

Indifference to traditional labor supply. This is the sharpest political break. Capital traditionally wants cheap labor. Labor traditionally wants protected labor. Orchestrators want no labor. Their entire thesis is that human labor is being replaced by compute. Adding human workers to the equation is, from the orchestrator’s structural perspective, moving backward. This puts them at odds with both the traditional left (which seeks labor protections orchestrators do not need) and the traditional right (which seeks expanded labor supply orchestrators do not want).

Minimal labor market regulation, maximum institutional stability. Orchestrators do not need minimum wage laws, overtime protections, or workplace safety regulations—not because they oppose worker welfare, but because they have no workers. What they need is predictable enforcement of the rules that do exist, stable infrastructure, and institutional environments where complex systems can operate without arbitrary disruption.

The result is a class that is politically orphaned. Neither party’s existing platform serves its material interests. The left offers labor protections for workers who do not exist. The right offers deregulation that may undermine the institutional stability orchestrators require. Both offer immigration policies calibrated to labor supply questions that are irrelevant to a class whose production model is post-labor.

This orphaned status has consequences. A class without articulated interests is a class that gets captured by whoever articulates interests for them. If orchestrators do not develop their own political voice, their structural position will be defined by capital (which wants to absorb them) or by the state (which wants to regulate them)—and both definitions will serve someone else’s interests.

Research Questions:

- What political interests does the orchestration class articulate, and do they align with its structural position?

- Does the class develop collective political action, or does it remain fragmented?

- Which existing political coalitions attempt to claim orchestrators, and with what success?

- How does the orchestration class’s indifference to labor supply reshape traditional political alignments?

3. Bargaining Power and the Platform Capture Threat

Right now, orchestration talent has enormous individual bargaining power. Firms depend on specific people for specific systems. Substitution is difficult because the knowledge is tacit and the market is illegible. This is the classic setup for bilateral monopoly: one buyer, one seller, high switching costs.

But bilateral monopoly is inherently unstable. It resolves when either:

- The buyer finds substitutes (automation, commoditization, training programs)

- The seller organizes collectively (guilds, unions, closed networks)

- The seller is absorbed by the buyer (equity, acquisition, employment)

The Suleyman prediction—full automation within 18 months—implies resolution via substitution. Platform capture implies resolution via absorption. The question is which dominates.

Platform capture is the existential threat. If OpenAI, Anthropic, or Amazon internalize orchestration into platform products—“click here to deploy enterprise swarm”—then the independent orchestration class vanishes the way independent SAP consultants vanished into Accenture. The defense is that platforms optimize for generality, safety, and scale, not for local optimization, edge-case exploitation, and competitive arbitrage. High performers will always outstrip defaults. But the history of technology platforms suggests that “always” is too strong a word. The correct claim is that high performers outstrip defaults until the platform gets good enough—and “good enough” is a moving target.

In practice, all three resolution mechanisms will operate simultaneously on different subsets of the class. Some orchestrators will be absorbed by Google. Some will form guilds. Some will be commoditized. The interesting question is the ratio—and whether the ratio shifts toward capture over time.

The WGA strike of 2023 succeeded in securing AI protections for screenwriters because writers had existing union infrastructure. Orchestrators lack this because their work is illegible, their employer relationships are ambiguous, and their identity is more entrepreneurial than proletarian. Whether alternative institutions emerge—guilds, DAOs, closed referral networks, reputation-based collectives—is one of the most directly observable research questions in this framework.

Research Questions:

- How dependent are firms on individual orchestrators?

- How easily can orchestration talent be substituted as tools improve?

- What determines the timeline for platform capture?

- Do alternative institutional forms emerge, and do they protect their members?

- What percentage of independent orchestrators are absorbed into firms within 1, 3, and 5 years?

4. Elite Reproduction and the Technocratic Aristocracy

A University of Illinois conference scheduled for March 2026 will explicitly examine “the possibility of an entirely new elite tier of class structure that is intelligent and technical but not human,” alongside the question of how “the technocratic class extends its grip over governance.” The academic apparatus is waking up to the question this framework has already formulated.

If the orchestration class reproduces itself—if the children of orchestrators become orchestrators because of social capital, tool access, and network effects rather than merit—then we are watching the formation of a durable technocratic aristocracy. If it does not reproduce itself—if the skill is too volatile, too dependent on individual cognition, too resistant to legacy transfer—then the class is transient.

The answer matters for policy design. A transient class requires transition support. A durable aristocracy requires democratic accountability. The two require different interventions, and getting the diagnosis wrong is expensive.

Research Questions:

- Do orchestration elites reproduce themselves socially?

- Are they becoming a durable technocratic aristocracy?

- Or is the class too volatile for intergenerational stability?

Part V: A Case Study in Orchestration

What the Work Actually Looks Like

Research frameworks are abstractions. Here is what orchestration looks like in practice.

I build agent swarms—systems where a meta-agent receives a high-level objective, decomposes it into a dependency graph of sub-tasks, spawns specialist sub-agents (a ContractBuilder, a BotBuilder, a DataValidator, a QualityAssessor), coordinates their parallel execution, and routes their outputs through validators and automated feedback loops. The systems are designed to compress development timelines from months to hours and to operate autonomously while I sleep.

The decisions that matter are not technical. They are architectural and political:

Decomposition judgment. When a meta-agent receives the objective “build a cryptocurrency arbitrage system,” the critical decision is how to decompose the goal. Which sub-tasks can be parallelized? Which have sequential dependencies? Where are the failure modes that will cascade? A wrong decomposition doesn’t produce a bad system—it produces no system. The agents execute confidently on a broken architecture and deliver sophisticated-looking garbage. The orchestrator’s job is to know which decompositions will hold before the agents run—and that knowledge is almost entirely tacit.

Failure diagnosis in probabilistic systems. When a 50-agent swarm produces an unexpected output, the failure could be in any agent, any handoff, any prompt, any validation step, or in the interaction between any subset of these. The failure mode of multi-agent systems is not “this agent made an error.” It is “the coordination protocol produced emergent behavior that no individual agent intended.” Diagnosing this requires a mental model of the entire system’s interaction dynamics—something no monitoring dashboard currently provides. The orchestrator feels where the failure is before they can prove it.

Risk arbitration. When the system works, the next decision is: do I trust it enough to deploy? In a financial system, a false positive loses money. A false negative loses opportunity. The tolerance for each depends on context that the agents cannot see—cash reserves, market conditions, regulatory exposure, personal risk appetite. The orchestrator makes this call. No one else can. No agent can.

These are not “prompting” skills. They are not “workflow design” skills. They are closer to what a military commander does when coordinating autonomous units in fog-of-war conditions—except the units are probabilistic, the fog is permanent, and the terrain changes every time a model provider ships an update.

Part VI: The Integrative Spine

Where the System Dynamics Converge

A. Extending Acemoglu’s Task Framework

Daron Acemoglu’s task-based framework is the dominant lens in labor economics for thinking about automation. His model distinguishes between automation (capital performing tasks previously allocated to labor) and new task creation (labor-intensive tasks that increase demand for workers).

Orchestration fits neither category cleanly. It is a new task created by automation that governs automation itself. This recursive structure is what makes it theoretically interesting. Showing that the task framework needs a third category—meta-tasks, governance tasks, coordination tasks—would be a genuine contribution to the literature.

The distributional question is where policy interest concentrates. An NBER working paper on AI and the skill premium makes a counterintuitive finding: because AI substitutes more for high-skill than low-skill labor, it may actually reduce the skill premium rather than increase it. But this analysis assumes a competitive labor market without intermediary layers. If orchestrators capture surplus through their position between capital and automated labor, the distributional picture changes entirely.

The key variables:

- Compute ownership: Who controls the infrastructure?

- Orchestration skill: Who can make it produce value?

- Organizational scale: Who can deploy at the level where returns become superlinear?

Which of these three captures surplus depends on the regime. In the current moment, skill dominates because it is scarce. As skill becomes commoditized or automated, surplus migrates to compute ownership. As compute becomes a utility, surplus migrates to organizational scale. Tracking this migration is the integrative research question.

B. Distributional Outcomes

Does orchestration widen or narrow inequality?

The honest answer: both, simultaneously, depending on the timescale and which layer of the orchestration hierarchy you occupy.

In the short run, orchestration widens inequality because the skill is scarce and the returns are superlinear. In the medium run, orchestration may narrow inequality among those who acquire it, because it is not gated by traditional credentials. In the long run, the answer depends entirely on whether the skill bifurcates into a high caste and a servant caste—and all evidence points toward bifurcation, not democratization.

C. Governance: The Control Problem as an Economic Problem

Who governs agent ecosystems in practice? Right now, orchestrators do. Their decisions are centralized, unauditable, and largely uncontestable. This is not a conspiracy. It is a structural consequence of illegibility: if nobody else can understand what the orchestrator is doing, nobody else can meaningfully oversee it.

This is not sustainable. But the alternatives—algorithmic auditing, institutional oversight, regulatory frameworks—all require that the skill become legible. And legibility is exactly what the skill resists.

The AI alignment research community frames this as the “control problem.” What they have not addressed is the labor market structure of control. Who does the controlling? How are they compensated? How are they organized? What happens when they are captured by capital or automated away? Alignment is not just an engineering challenge. It is a distributional challenge—a question of who holds power in systems where human judgment is increasingly mediated by probabilistic tools.

Part VII: Making This Real—Empirical Anchors

A research framework is only as good as its operationalization. Here is how scholars would actually study these questions:

1. Field Studies

- Ethnographies of AI-heavy firms, focusing on the division of labor between orchestrators and other roles

- Embedded observation of orchestration teams—how decisions are made, how failures are diagnosed, how knowledge is transferred

- Case studies of solo orchestrators operating autonomous systems, documenting the tacit knowledge that governs their decisions

2. Labor Market Data

- Contract rates and fee structures for orchestration work

- Hiring patterns: which firms are hiring, what signals they use, what premiums they pay

- Talent migration networks: where orchestrators come from and where they go

3. Network Analysis

- Referral graphs: who recommends whom, and how does reputation flow?

- Collaboration networks: who works with whom, and how does skill transfer?

- Exclusion patterns: who is systematically absent from these networks, and why?

4. Experiments

- Blind orchestration trials: can evaluators distinguish skilled from unskilled orchestrators by output alone?

- Performance audits: do benchmark tasks predict real-world orchestration performance?

- Signal manipulation studies: do certain signals (GitHub contributions, referrals, public demos) actually predict competence?

5. Longitudinal Tracking

- Career trajectories: how long do orchestrators remain in the role? Where do they go?

- Skill decay: how quickly does orchestration competence depreciate at different levels of abstraction?

- Capital absorption: what percentage of independent orchestrators are absorbed into firms within 1, 3, and 5 years?

Funding Pathway: Anthropic’s Economic Futures Program, launched in June 2025, offers $10,000–$50,000 rapid research grants specifically targeting empirical research on AI’s economic impacts—including labor market effects, productivity, and distributional consequences. This framework addresses multiple categories they explicitly call out. The program is designed to produce results within six months, compatible with the targeted empirical work this agenda requires.

Part VIII: The Suleyman Gap

Suleyman and Amodei are both declaring the end of professional classes. Neither is addressing the layer that replaces them.

That creates a clean research wedge:

If professional labor is collapsing, and capital owns the models, who governs the transition?

This framework says: the answer is temporarily “orchestrators.” And the open question is whether that “temporarily” is a brief premium that dissolves into automation or a generational restructuring of who holds power in an automated economy.

Suleyman will not address this. Amodei will not address this. The discourse gap exists because acknowledging the orchestration layer undermines the narrative that automation is smooth, inevitable, and distributionally neutral.

It is not. The distributional consequences are profound. And they are being determined right now by a class that has no name, no institution, and no accountability structure.

Conclusion: The Meta-Question

If you want the philosophical anchor—the sentence that makes all of this cohere:

Is orchestration a new form of labor, a transitional ruling class, or the last human chokepoint in automated production?

Every section above feeds into answering that question.

From an academic perspective, this framework is powerful because it:

- Bridges labor economics (Acemoglu, Autor, Brynjolfsson & McAfee), signaling theory (Spence), superstar economics (Rosen), organizational learning (Wenger), and AI alignment research (Anthropic, DeepMind, MIRI)—fields that rarely talk to each other

- Has immediate empirical sites—the firms, the communities, the hiring markets are all observable now

- Connects micro to macro—individual skill formation to system-level inequality

- Extends existing theories instead of rejecting them, while identifying where they break

From my own position, it does something else. It turns a lived experience into a falsifiable research object.

Not “I’m special.” But:

What happens when a society depends on a tiny, illegible, unstable competence layer that sits between the models and the outcomes?

That is the question. The framework above makes it answerable. The clock is running. And the answer matters for everyone—not just the orchestrators, but the billions of people whose economic futures depend on decisions being made right now by a class that does not yet have a name.

Sources & Further Reading

Academic Literature

- Acemoglu, D. & Restrepo, P., “Automation and New Tasks: How Technology Displaces and Reinstates Labor,” Journal of Economic Perspectives (2019)

- Acemoglu, D., “The Simple Macroeconomics of AI,” NBER Working Paper (2024)

- Brynjolfsson, E. & McAfee, A., Race Against the Machine: How the Digital Revolution is Accelerating Innovation, Driving Productivity, and Irreversibly Transforming Employment and the Economy (2011)

- Koenig, F., “Technical Change and Superstar Effects: Evidence from the Rollout of Television,” American Economic Review: Insights (2023)

- Lave, J. & Wenger, E., Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation (Cambridge, 1991)

- Piore, M., “Tacit Knowledge and the Future of Work Debate,” MIT Working Paper (2025)

- Rosen, S., “The Economics of Superstars,” American Economic Review (1981)

- Spence, M., “Job Market Signaling,” Quarterly Journal of Economics (1973)

- Wenger, E., Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity (Cambridge, 1998)

AI Alignment & Control

- Anthropic, “How We Built Our Multi-Agent Research System” (2025)

- Anthropic, “Preparing for AI’s Economic Impact: Exploring Policy Responses” (2023)

- Stanford Digital Economy Lab, “Aligned with Whom? Direct and Social Goals for AI Systems” (2024)

Empirical Studies

- Chandar, B. et al., “Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of AI,” Stanford Digital Economy Lab (2025)

- Deloitte, “Unlocking Exponential Value with AI Agent Orchestration,” Technology Predictions 2026 (2026)

- “Beyond Training: Worker Agency, Informal Learning, and Competition,” Norwegian study on skill formation (2025)

Stratification & Inequality

- “Cognitive Castes: Artificial Intelligence, Epistemic Stratification, and the Rational Elite,” arXiv (2025)

- “A Workers’ Inquiry in Decentralised Autonomous Organisations,” Internet Policy Review (2026)

Author’s Prior Work

- Maddox, T., “The Competence Insolvency” (2025)

- Maddox, T., “The Human-Free Firm: Why Full Automation Hits a Wall” (2025)

- Maddox, T., “The Tokenization of Existence: Why Universal Basic Compute Is a Trap” (2025)

- Maddox, T., “The Triage Loop: From Static Distribution to Homeostatic Social Control” (2026)

- Maddox, T., “Securitized Souls: Capital Without Capitalists” (2025)

- Maddox, T., “The Post-Labor Lie: Why the End of Work is the End of Human Economic Agency” (2025)

- Maddox, T., “Navigating the L.A.C. Economy” (2025)

Ask questions about this content?

I'm here to help clarify anything